- Hurrah! US inflation is still falling, slightly.

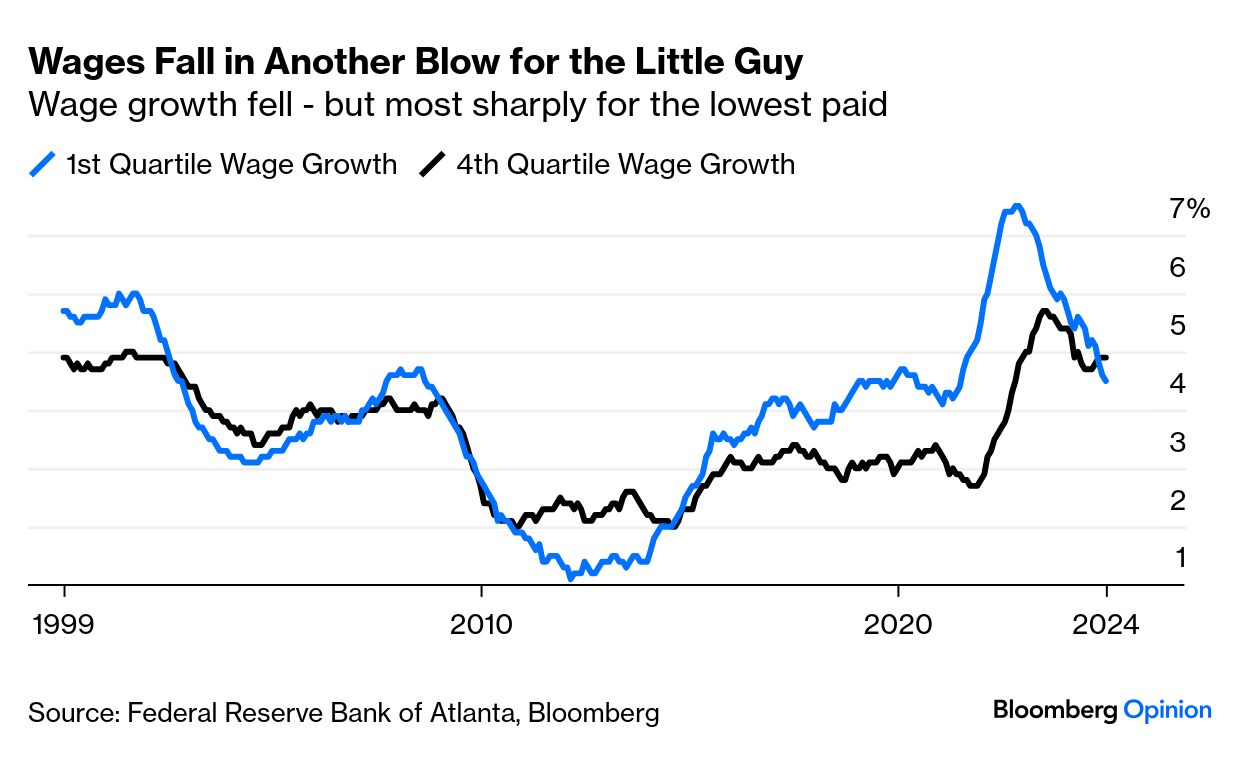

- Wage rises are also coming down, particularly for the less well-paid.

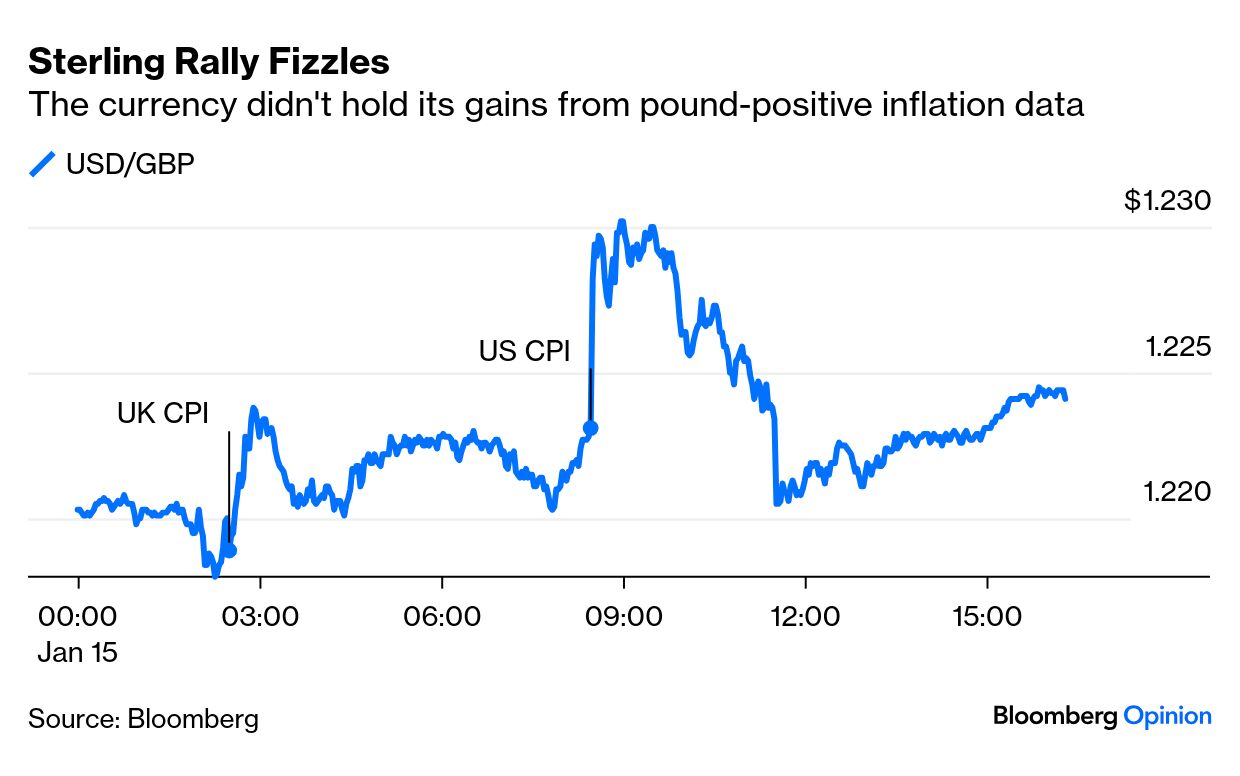

- Three cheers for the UK, whose difficulties ease a little — although the pound isn’t convinced.

- More cheers for Wall Street, where banks made a killing in the fourth quarter.

- With the Biden administration’s inflation record in the books, we can confirm: The cost of living rose.

- AND: Farewell to the sad and brilliant clown Tony Slattery.

And, breathe. Wednesday’s US inflation data showed that the rate of price rises was falling, and that pressure was a bit milder. That it led to a massive “risk-on” rally is testament to the amount of nerves that had developed. While the numbers did indeed show inflation coming under control a slightly greater deal than had been expected, they left no clarity about the way ahead. Breaking down the CPI into its four main elements reveals that ongoing inflation is more or less entirely about services, as has been the case for a while. Food prices are still edging upward, but nowhere nearly as fast as in 2022; energy and goods prices are largely quiescent: More detailed statistical measures confirm that inflation is coming down, but very slowly and it remains above target. Both the trimmed mean (excluding outliers on either side) and median versions produced by the Cleveland Fed show very slight declines in an ongoing, painfully slow progress toward the Federal Reserve’s 2% target. Disinflation is petering out, but at least hasn’t reversed: The Atlanta Fed’s measure of sticky prices that are particularly difficult to change shows a more encouraging fall, particularly in the last three months, but again is still uncomfortably above target: As for the “Supercore” measure of services inflation excluding shelter, a favorite of the Fed itself, a slight decline last month still leaves the overall annual increase unacceptably high at a little above 4%: All of this followed producer price inflation announced Tuesday, which was lower than expected but still ticked upward.

The Atlanta Fed published arguably the Fed’s most significant news Wednesday, although it would be unwelcome to many. Its monthly tracker of wage rises, based on census data, showed a decrease in wage inflation. This was almost entirely because of low raises for the first quartile of workers (the 25% with the lowest wages), whose raises dropped below those of the highest quartile for the first time in a decade:  This is good for the Fed’s inflation fight, as poorer people are more likely to spend any wage increase. It’s not great news in any other way. The response in the rates market was to increase the chance of cuts in the fed funds rate this year, but not by all that much. Bloomberg’s World Interest Rate Probabilities function now prices one 25-basis-point cut this year as a certainty, while the odds of a second have risen to 57% from 24% since the CPI was published — exactly where they were before the strong US unemployment numbers were released last Friday. For all the excitement, the market sees the short-term outlook for the Fed as unchanged by the latest dose of big numbers. The massively positive reaction was driven by the preceding trepidation. In the last few weeks, the resumption of rate hikes has begun to look a real possibility. It’s still plenty possible, but made less likely at the margin by the latest data. The rally in stocks testifies to just how scared investors in risk assets were about hikes, and how dependent risk markets remain on continuing cheap money. The rally was close to universal, but one of the most interesting tells came in the way that consumer discretionary stocks far outpaced staples, a classic sign of risk appetite and a belief in a cyclical recovery: Bond yields dipped worldwide. But everywhere the fall looked like a correction after a big advance — not, yet, a turning point: The most interesting case was the UK. Nobody had more reason for delight about the US inflation numbers than Rachel Reeves, the chancellor of the exchequer. The new Labour government’s very hesitant first six month have culminated in sharp selloffs for gilts, sharply increasing UK borrowing costs. But British inflation data, announced a few hours before the US, were lower than expected. That gives the Bank of England more freedom to cut rates. Then the US data fed into a great gilts rally. The 10-year yield fell by the most since 2023: That begins to diminish the uncomfortable similarities to the gilts market implosion that ended the Liz Truss premiership in 2022. It also allowed sterling to rally (though that didn’t last):  Why not? Part of the problem is, as Marc Chandler of Bannockburn Global FX says, that speculation is rife that Donald Trump will celebrate his inauguration next Monday (when US markets will be closed for Martin Luther King Day) with a raft of dollar-positive executive orders. Nobody wants to be short the dollar before that. Investors took the opportunity of a dollar reversal to buy more. The lack of appetite for sterling is a problem, because the UK has a relatively small and open economy, and big deficits, and is therefore “painfully reliant on the kindness of strangers,” as Ian Harnett of Absolute Strategy Research puts it. The inflation numbers on both sides of the Atlantic relieve the threat of a Truss crisis somewhat. The risk is more of a slow burn in which the UK is boxed in and unable to get out of its fiscal constraints. Before the inflation numbers, Wall Street greeted some great news about itself. Big banks’ optimism that Trump’s regulatory regime will be pro-business helped translate into great fourth-quarter results. The Big Four (JPMorgan, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Wells Fargo) posted stellar full-year results, second-best only to the stock market boom year of 2021. The KBW Bank Index reached back to the heights witnessed in the aftermath of Trump's reelection, an outcome further fueled by the inflation numbers: Is Wall Street’s excitement justified? Sean Ryan of FactSet argues that rates were a positive in the fourth quarter, as the steepening yield curve made lending operations more profitable. But rising yields will exacerbate losses, hurt mortgage banking results, and make it harder to refinance commercial real estate loans: Regardless, earnings reported so far feed hopes that bank stocks — badly rocked by the regional banking crisis of early 2023 — can return to outperforming the S&P 500 once more. Bank of America analysts detail that bank stocks are among the few sectors to trade at a discount compared to their pre-pandemic medians: We expect this discount to dissipate and would argue for improved valuations for bank stocks vs. pre-pandemic levels given a more positive interest rate backdrop (relative to zero-bound for most of 2009-2020) which should benefit banks with strong deposit franchises, a more balanced and predictable regulatory regime, and a Trump agenda that is likely to encourage domestic capex.

Trump’s agenda has almost universal approval in the financial sector. Next come the regional banks. They’re projected to report an improvement in earnings of $3.1 billion compared to a $3.8 billion decline in the previous year, according to FactSet. The big banks’ numbers drove their best day since the immediate post-election euphoria: Another tell-tale sign of optimism: Deal speculation is back. Bank of America’s analysts warn that potential larger regional bank buyers are anxious not to overpay, but that doesn’t mean a lack of interest. With regulatory burdens increasing when a bank’s assets pass $100 billion, they suggest the consolidation will accelerate among banks with total assets of between $20 billion and $60 billion, which can buy without breaking the threshold. Regulation — or, the sector’s backers hope, the relative lack of it — is the key to the optimism. —Richard Abbey The American public’s judgment on the Biden administration’s inflation record was clear and damning. He let prices get out of control, and didn’t restore living standards once the worst rises were over. For that, in large part, the Democrats were evicted from the White House. Now that the last complete month of the Biden administration is in the books, we can get a good handle on that judgment Food and energy are excluded from “core” measures tracked by central bankers for the good reason that monetary policy has little ability to move them. However, people have to buy them. Increases in what we might call the “anti-core” (food and energy combined) are politically salient. As demonstrated by the following chart, drawn up from Bureau of Labor Statistics data by our data editor Carolyn Silverman, anti-core prices spiked in 2022 in a way not seen since geopolitical shocks in the 1970s. That’s now been brought back under control, but the level of food and energy prices hasn’t come back down: Another way to look at this comes from the team at Strategas Research Partners, who produced a “Common Man” inflation index, based on the non-discretionary items that most people have no choice but to buy — food, energy, shelter, clothing, utilities and insurance. Wages ran ahead of this version of inflation under Trump 1.0, and slipped badly behind under Biden: Breaking down inflation into its most important constituents, this is what happened to prices during Trump’s first term. Average earnings grew fast enough to outstrip rises in a range of different prices: Under Biden, the story is different. Earnings have overtaken rises in prescription drugs, and in goods broadly defined. By the end of his four years, the price of used cars — center of the greatest alarm when the inflation spike was at its worst — had risen no more than earnings. Food, services and shelter, however, have all exceeded rising earnings: There’s room to argue over how much of the inflation since 2020 has truly been the fault of Biden and his administration. But when voters complained that it grew more expensive to make ends meet under his watch, they were right. This week saw the extremely sad death of Tony Slattery from a heart attack at 65. Not really known outside the UK, he was a president of the Cambridge Footlights (where his co-actors included Emma Thompson and Hugh Laurie) who became possibly the most ubiquitous comedian on British TV and film in the early 1990s. Then he had a terrible breakdown and spent the rest of his life ravaged by mental illness. For a taste of his improvisatory brilliance, try this and this and this and this. Rest in peace, Tony.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Javier Blas: Trump's Folly? Greenland for Critical Minerals Is Utter Nonsense

- Paul J. Davies: Jamie Dimon’s Succession Race Just Lost a Top Candidate

- Marc Champion: Gaza Ceasefire Deal Is a Win for Trump

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN . Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |