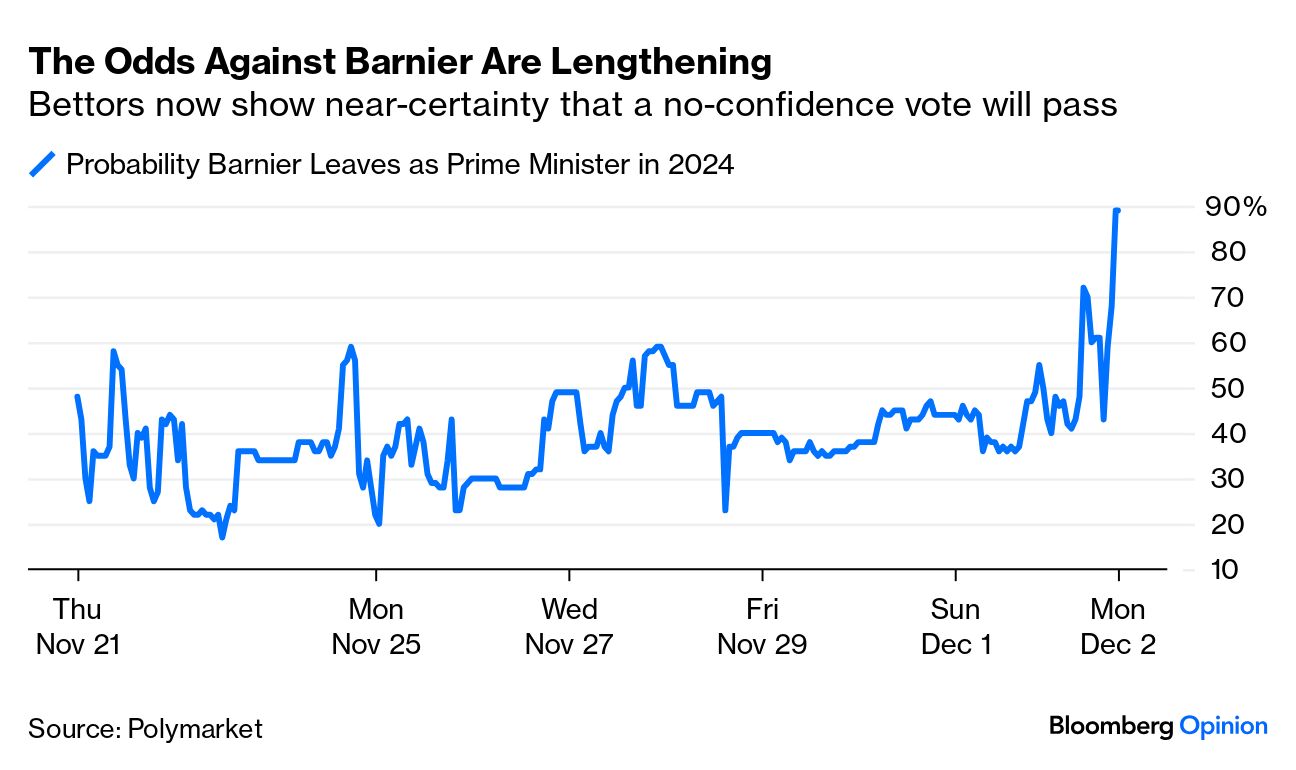

| Push is coming to shove in France. The urgent question now is how its steady slide into political dysfunction will affect the rest of Europe at a time when the crucial relationship with the US is unclear. Monday saw Prime Minister Michel Barnier resort to a legal maneuver to force through his budget, which allowed the opposition to call a vote of no confidence. An unholy alliance of the hard right and hard left — accounting for close to two-thirds of the National Assembly — say they’ll support the vote, and his chances of political survival have more or less evaporated. The Polymarket betting site now sees only a 10% chance that he’ll still be prime minister at year-end. That’s a rapid deterioration; his chances of survival were put at 80% just last week:  An end to the deadlock is nowhere near, as parliamentary elections cannot be held until July. President Emmanuel Macron will need to nominate a new premier who will presumably be similar politically to the centristBarnier, and with no agreement on a budget, the 2024 arrangements will simply be rolled forward. Macron’s mandate runs until 2027. Should he choose to resign before that, the chances are growing that the choice presented to the electorate in the second round of a presidential election would be between Marine Le Pen of the hard right and Jean-Luc Melenchon of the hard left. France has become virtually ungovernable. Loss of confidence has pushed up borrowing costs, with 10-year French OATS now yielding 88 basis points more than German bunds: There will be takers when yields are this attractive. But it’s hard to identify any source of demand that would thwart the spread from widening further. As Barclays Plc shows in this chart, both domestic banks and foreign official buyers were already showing declining interest: But crucially, the contagion to the rest of the euro zone has so far been minimal — suggesting that the European Central Bank’s promise to act as a lender of last resort, made under duress in 2012, is still having a powerful effect. When the bloc’s sovereign debt crisis broke out in 2010, there was thought to be a real solvency risk attaching to countries at the European periphery, particularly the so-called PIIGS — Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain. This time around, the extra spreads that they must pay to investors compared to bunds have remained very stable. There is certainly nothing of the highly correlated lurches across the region that characterized the start of the last decade:  “The good news is that the periphery is not infected,” said Mathieu Savary of BCA Research. “That confirms that the market can differentiate between a specific French problem and a broader problem for the periphery. The extremely ugly dynamics are reduced and the credit for that goes to the ECB for playing the role of a credible lender of last resort.” But while the issue is not solvency, as it was 15 years ago, Jean Ergas of Tigress Financial Partners cautions that the problem “is yet more chipping away at the euro zone, its credibility, and the role of the euro as a reserve currency.” That might imply buying French bonds at their current discount, but the catalysts must await resolution of political issues elsewhere. First, Germany goes to the polls early next year, contemplating a big change to liberalize fiscal policy. In the wake of the Global Financial Crisis, the country passed what became known as the “debt brake,” limiting each year’s deficit to 0.35% of GDP. The brake was deliberately given full constitutional force to make it hard for politicians to backtrack.

That said, the leaders of both the center-right Christian Democrats — in a commanding position in the polls — and the incumbent Social Democrats favor more spending. Whether voters deliver a big enough coalition to overturn the brake now becomes a crucial question for markets. Cedric Gemehl of Gavekal Research said that a radical overhaul of the brake was a long shot, but no longer unthinkable. “This creates upside risk for growth in Germany and the EU as a whole,” he said. “It also means that even more bonds may be issued by European governments, which will add to the upward pressure on yields.”

The other crucial issue is the return of Trump.  The Macrons and Trumps on Bastille Day 2017. Photographer: Stephen Crowley/AFP/Getty Images “Europe is essentially a play on global trade,” says Savary, meaning it potentially has much to lose from a trade war. However, he also sees good odds on a potential grand bargain. If the EU offered to reduce its current big surplus with the US by promising to spend 2% of gross domestic product on defense — a repeated Trump demand — and entered into a deal to buy US liquefied natural gas, he suggested that the European economy could be much improved, with the benefit of reducing vulnerability to Russia. A mercantilist deal along these lines could work for both parties, and provide a catalyst for buying European, and even French, assets.

Christine Lagarde of the European Central Bank has already tried to drum up support for a policy to deal with the issue. But how plausible is such a grand bargain? Ergas is much more skeptical, pointing out that Trump seems far more preoccupied by Asia and the Middle East, and that he has registered his dislike for Europe. Until Trump chooses to recast that trading relationship, it will be hard for French assets to stage much of a recovery.

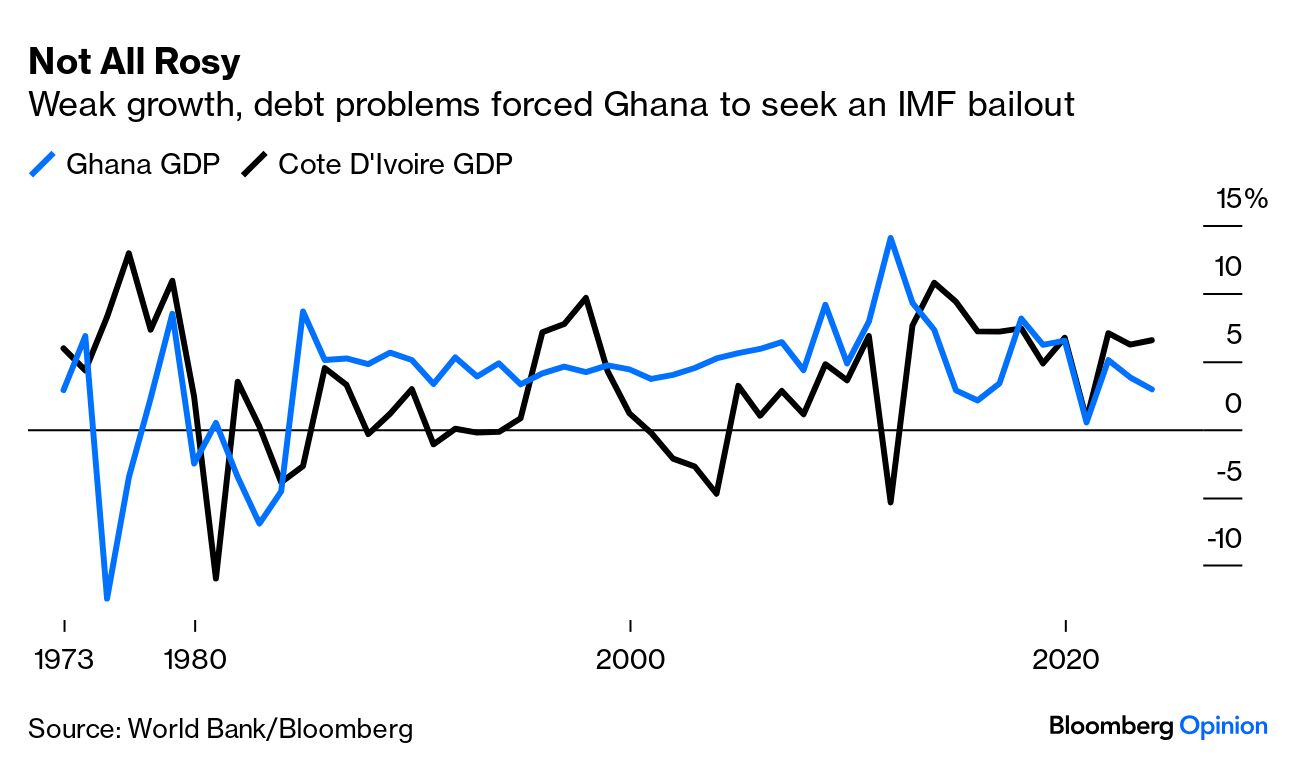

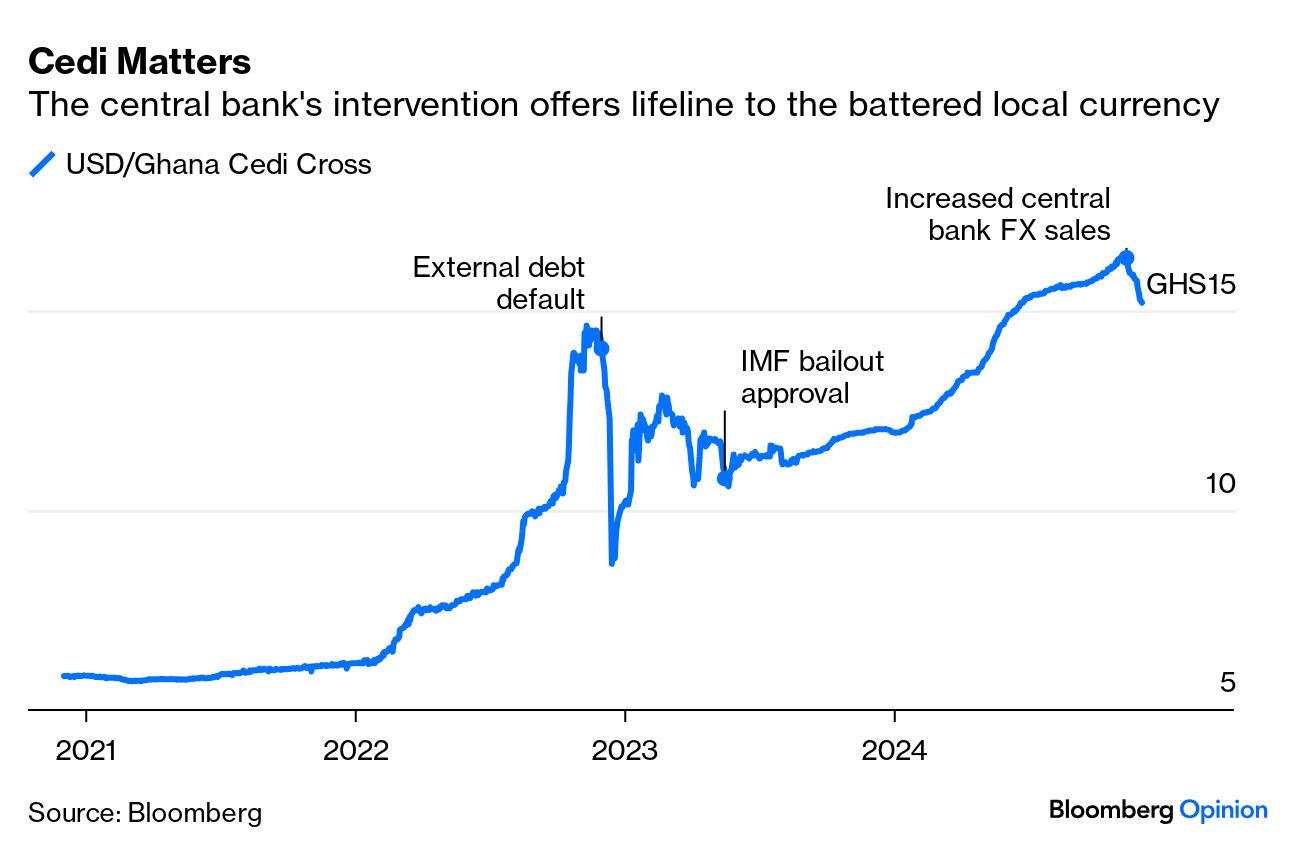

| | | Welcome back to Richard, who has returned from a family visit to Ghana with this update on one of sub-Saharan Africa's most stable democracies, which goes to the polls on Saturday. The issues it faces are painfully reminiscent of the problems in Europe, and the contest is on a knife-edge. Two candidates, the current Vice-President Mahamudu Bawumia and former President John Dramani Mahama, are in a virtual dead heat, with the odds slightly favoring the latter. Since 1992, no ruling party has secured a third consecutive four-year mandate, a jinx Bawumia's New Patriotic Party is seeking to break. However, he faces a tall order of convincing disenchanted voters reeling under the high cost of living, rising youth unemployment in a population of 34 million, and worsening poverty levels. Post-pandemic growth has been sluggish, with debt problems pushing the West African country to seek a $3 billion International Monetary Fund financial support in 2023. Ghana continues its record of 40 years of positive economic growth, as measured by the World Bank. That has compared favorably over much of that time with neighboring Cote d’Ivoire, but in recent years Ghana has begun to lag:  Default and the restructuring — expected to lower debt owed to bondholders by $4.7 billion — effectively shut Ghana out from international debt markets. That starved the country of the steady inflow of foreign exchange crucial to providing support to the local currency, the Ghana cedi, which has lost more than 33% of its value since the start of 2023. That’s a serious problem for Bawumia, an economist and former deputy central bank governor. However, the cedi has regained some stability ahead of the elections following the central bank's increased forex intervention:  Is the intervention sustainable? Probably not. At best, it’s merely a quick fix to a problem that requires a structural shift in the economy, which has been affected by droughts. The World Bank suggests needed reforms include strengthening the insolvency regime, allowing greater access to finance, and creating a legal and regulatory system to encourage foreign direct investment. Still, the troubles of the current administration don’t mean an easy path to victory for the opposition. Mahama is promising reforms to improve living conditions, prioritizing access to primary health care, as well as massive infrastructure development. But he has an incumbent’s disadvantage, too, as the widespread power outages and corruption scandals that led to his failed re-election bid eight years ago still haunt his candidacy. Given the economy's precarious position, how realistic are the candidates’ promises? The Accra-based Institute for Fiscal Studies’ Leslie Dwight Mensah sees limited room for the next president to deliver on all of them: Despite the financial relief obtained from the IMF, Ghana continues to face a restricted fiscal space, with still-elevated debt service obligations and a persistent buildup of energy sector liabilities. This, together with the country's commitments under the IMF program, will constrain the fulfillment of the manifold electoral pledges made during this campaign. If there's any room for maneuver, it lies in a dramatic increase in public revenue, which is not realistically in prospect at the moment.

Following a protracted debt restructuring, foreign investors are keeping tabs on Saturday's elections. The performance of two benchmark eurobonds indicate a degree of calmness. The price of the 2029 bond with a 5% coupon rate has inched up 0.65%, while the longer-dated one with similar maturity is trading only 0.38% lower: If anything, investors will want to see more fiscal consolidation and restraint. Given Ghana’s history of slippages in election years, Standard Chartered Bank Plc’s head of Africa Strategy Samir Gadio says that there are concerns about whether the cycle can really be broken when the budget is presented early next year: However, he adds: Beyond that, a lot of investors turned somewhat constructive on Ghana’s external bonds as a potential trade for 2025 after the restructuring. Given that the external debt service burden and debt burden as a whole are now more manageable, we'll have to see whether this helps bonds actually perform stronger in 2025.

Hanging over it all is the current IMF program, which runs until 2026. Theophilus Acheampong of the IMANI Center for Policy and Education, argues that implementing either party’s spending plan would likely mean Ghana breaching its debt sustainability thresholds. “The winning party will likely scale back on its overambitious promises lest the markets punish it again,” he says.  Mahama hopes to renegotiate the IMF program to reduce taxes. Photographer: Ernest Ankomah/Bloomberg Oxford Economics’ Jervin Naidoo sees a win for the opposition as a base case, adding that their proprietary models predict the economy will likely fare slightly better under Mahama, whose promise of a social safety net could buy him more time and provide wiggle room. However, as Emmanuel Macron and Michel Barnier are finding out in France, the space to juggle the demands of investors and the public can vanish very quickly. —Richard Abbey Maria Callas would have been 101 today. The great diva is about to be portrayed by Angelina Jolie in a biopic. The facts of her life are dramatic and tragic; to remember why people listened to her in the first place, try watching her as Carmen, or Tosca, or the

Countess in the Marriage of Figaro, or this unbearably beautiful aria from Berlioz’s “Damanation of Faust.”

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close.

More From Bloomberg: - Nir Kaissar: McDonald’s Inflation Tug of War Should Worry More Companies

- Bill Dudley: The Fed’s Next Big Policy Rethink Needs Rethinking

- Shawn Donnan and Anna Wong: What Trump’s Next Trade War Could Look Like, a Guide

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |