| One of the pleasures of being back in England is that I can start the day listening to BBC Radio 4’s “Today” program, which has set the national agenda for many decades. With threats of nuclear war rising over Ukraine, the headline news this morning was that UK consumer price inflation had risen to 2.3%, more than expected and “the highest since April.”

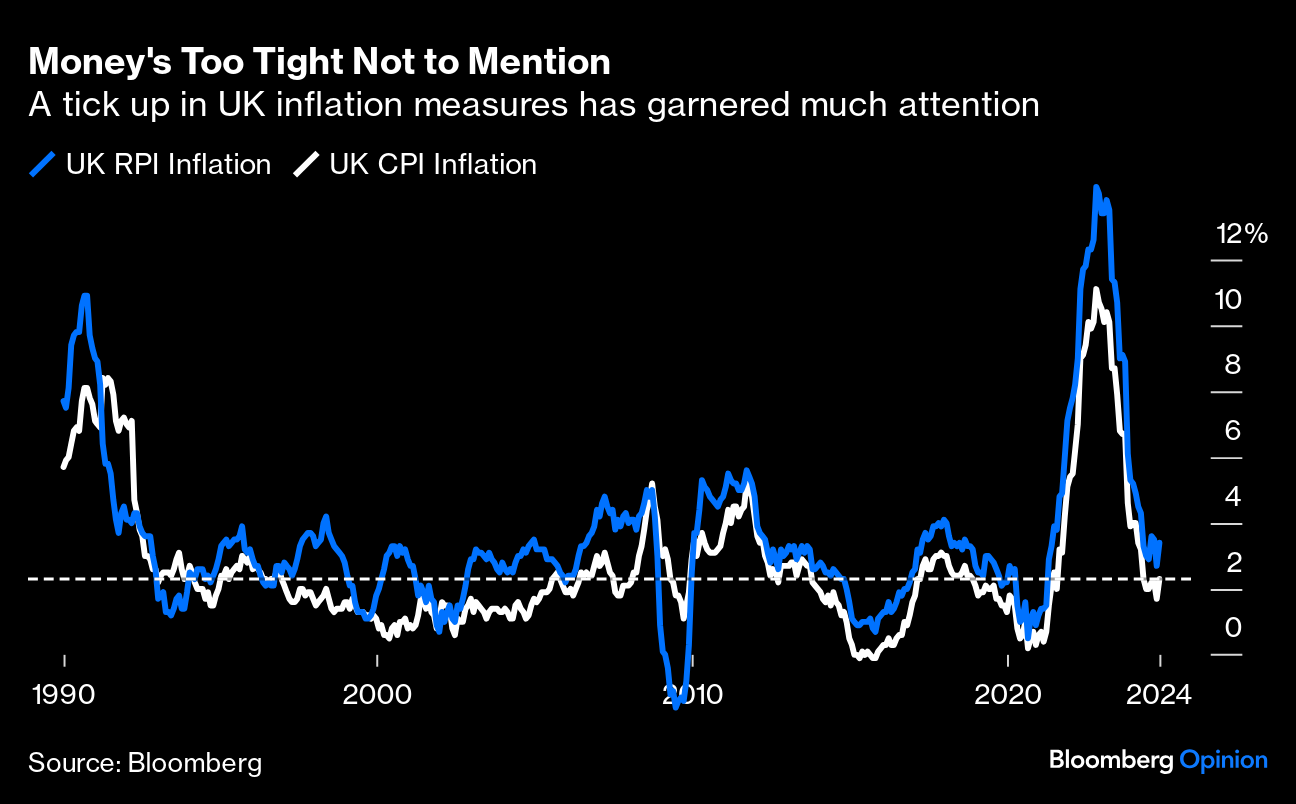

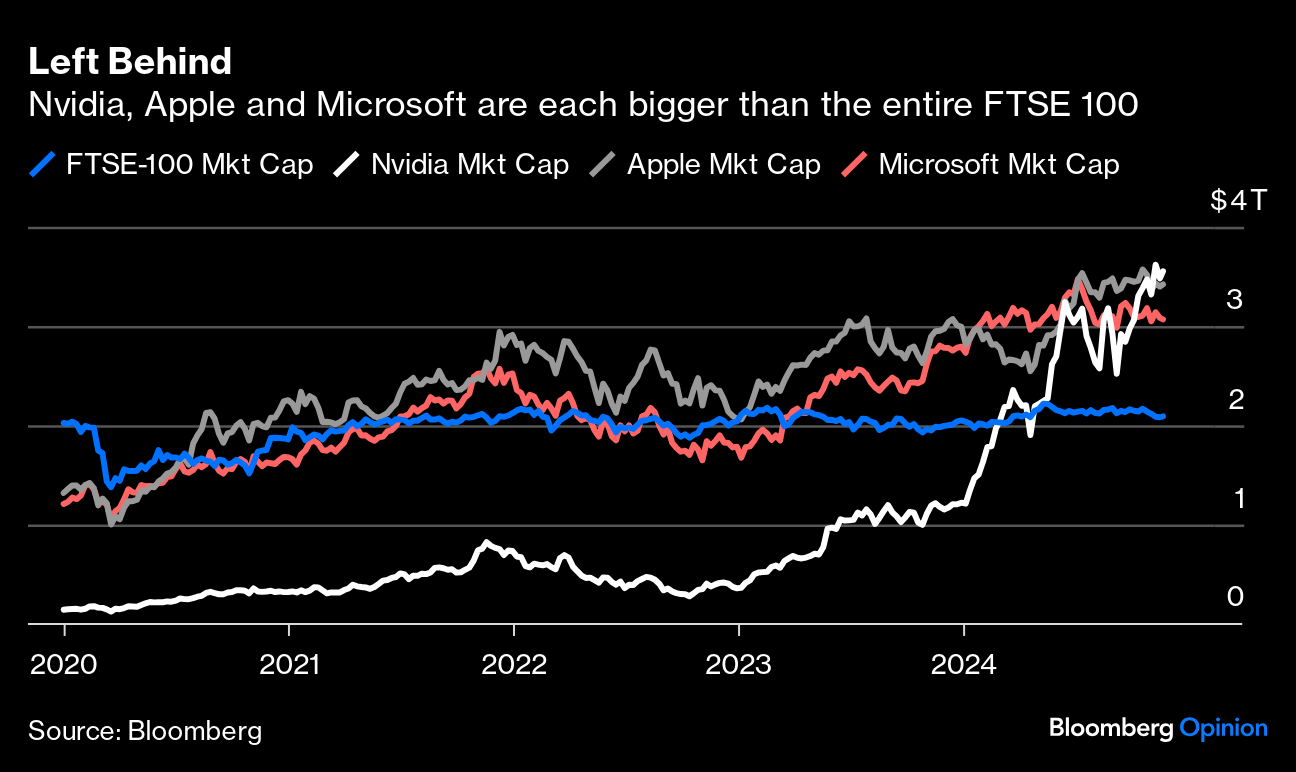

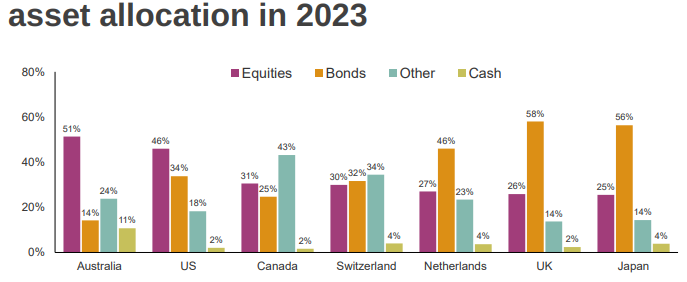

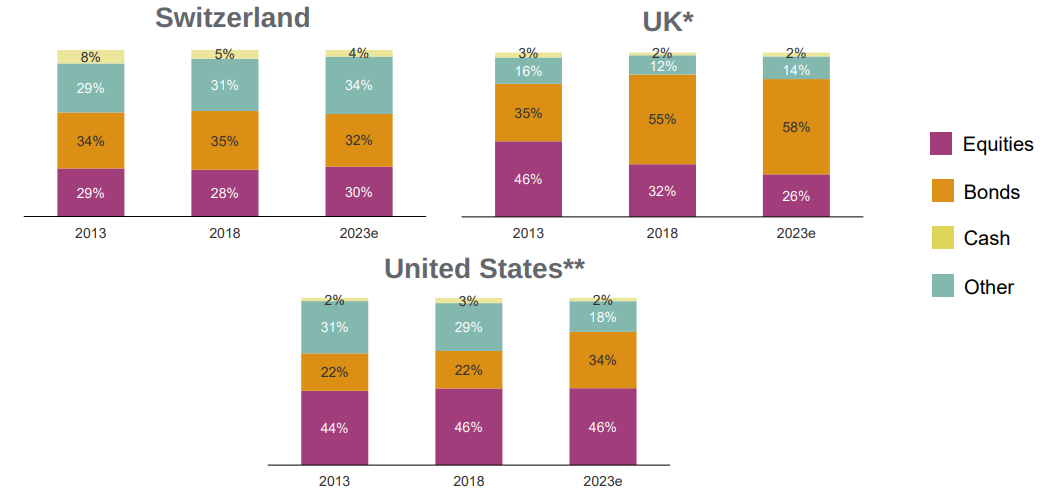

That was a telling choice of priorities. To add context, this is how UK CPI, and the separate Retail Price Index that has been calculated for longer and is still used as the basis for various index-linked benefits, have moved since 1990:  In the greater scheme of things, this rise in inflation, driven by a wholly predictable increase in gas prices after government subsidies were reduced, doesn’t look such big news. The fact that it received this much attention is worrying for central bankers. The former deputy chairman of the Federal Reserve, Alan Blinder, once defined price stability as “when ordinary people stop talking and worrying about inflation.” So price instability is still with us. That’s reflected in market expectations for the Bank of England. Gilt yields rose sharply after Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ budget announcement at the end of October, and that bond market move has persuaded the overnight index swaps market to cut back on predictions of cuts in the Bank Rate. The shift since the budget has been noticeable, and suggests that traders no longer expect rates to get as low as 4% in this cycle: Inflation is dangerous for governments, but there is a less immediate yet more profound problem for Reeves and the new government. The UK’s stock market is stagnating. This chart, suggested by Bloomberg colleague Sam Unsted, shows that the market value of the FTSE 100, capturing the biggest UK-quoted companies, has moved sideways in dollar terms for five years. Meanwhile, the biggest tech platforms have grown so much that each of Apple Inc., Microsoft Corp. and Nvidia Corp. is on its own worth more than the entire index:  For UK investors, the easy solution is to place capital in the US, and plenty of investment products help them do that. But that intensifies the problem for Reeves, which is the dearth of capital for Corporate UK. A remarkable report by the Thinking Ahead Institute shows that the UK’s pension funds put 56% of their assets into bonds. This is roughly equal to deflation-ridden Japan, but far higher than in the rest of the world’s seven biggest pension systems. Australian pensions have roughly double the equities weighting as UK counterparts:  Thinking Ahead Institute The problem has intensified in the last decade. This Thinking Ahead chart shows pension systems’ asset allocations in 2013, 2018 and 2023 for the US, Switzerland and the UK. British bond allocations weren’t far out of line 10 years ago, but now look extreme:  Thinking Ahead Institute This can only have involved a deliberate move out of stocks and into bonds. Equities have outperformed so much over the last decade that it’s quite a feat for pensions to have increased their weighting in bonds so much. The relative performance of the Bloomberg Aggregate for UK bonds and the FTSE-All Share index shows that if managers had stood back, their equity weightings would have grown very significantly: The move into bonds reduces risk and ensures funds can match their liabilities to pensioners, both important goals. But it has come at the expense of capital for productive investment in the UK. With the fiscal situation strained, the government cannot prime the pump, even if it wanted to. So the imperative is to make whatever technical changes are needed to persuade more money to invest at home, starting with the pension system. Without this, the country will have difficulty generating growth needed to lance the pain of higher price levels. To her credit, Reeves is trying to do something about it. Her Mansion House speech last week included ambitious plans to consolidate the highly fragmented system into a few giant pension funds that can use their scale to take greater risks, as is seen in particular in Australia and Canada. She’s had a positive initial reception. But this is a long and difficult process and it’s easy to misdirect capital. It also can’t be allowed to turn into de facto protectionism in which the government forces savings into unimpressive UK-based projects. Colleague John Stepek describes this as a “slow-motion pension revolution,” and it’s difficult to make any changes to long-term investments quickly. Somehow, the government will need to summon the patience to get this right, and the continued anguish over price rises won’t make that any easier. This hole Britain took a long time to dig, and it will take a while to climb out of it. It’s difficult to know how much to trust employment data in the wake of the pandemic. The overall jobless numbers in the US have so far thwarted predictions of an imminent recession. With Donald Trump taking office with an agenda virtually certain to spark fresh growth in the short term, it’s reasonable to worry more about overheating than any slowdown. But there are two charts of the US jobs market that make me go hmmmm. First, the Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker series measures wage rises for those who switch jobs and those who stay. Wage rises are usually bigger for switchers, as this is generally the reason they decide to move in the first place. Stayers get higher raises, as a rule, only when the economy is really tough and the switchers are moving because they have to. The “switcher’s premium” hit an all-time high in 2022 as the Great Resignation put negotiating power emphatically in the hands of employees. That’s declined; it’s now lower than the norm for the last quarter-century, and earlier this year even went negative: For another disquieting sign, the JOLTS (Jobs and Labor Turnover Survey) shows that the rate of quitting, which peaked at a remarkable level following the pandemic, is now back below its norm. The quit rate is where it was in early 2008, when the economy was beginning to weaken alarmingly. This looks like further evidence that workers are finding that the labor market is turning against them: As Peter Tchir of Academy Securities says, “My take on the quit rate is that it is ‘crowd-sourced’ data. Every individual has a pretty good idea about their own job prospects, and that gets reflected in the quit rate.” There are problems with low response rates and other distortions post-Covid, but this seems a wise assessment. Amid much anxiety about continuing inflation, reflected in spades by the result of the US election, it looks like workers are inhabiting a world where finding a job is getting difficult. This doesn’t mean that it’s safe to ignore inflation, because it isn’t. The pendulum has swung against major rate cuts for good reason. But it’s important to question assumptions, and these charts certainly raise questions. After more than 1,000 days of hostilities, the markets are accustomed to the possibility of escalation in the Russia-Ukraine war. Still, recent developments — Kyiv’s striking targets in Russia with US-sanctioned missiles, and President Vladimir Putin authorizing use of nuclear weapons in response to non-nuclear attacks supported by nuclear-armed states — are capable of taking the conflict to the next, unthinkable level. Unsurprisingly, the Kremlin’s move has drawn condemnation. Concerns about Russia unleashing its nukes spiked shortly after the invasion in February 2022, driving market turmoil. Since then, such concerns have droned in the background. As shown from this chart tracking news headlines mentioning “nuclear weapons,” Putin’s new policy caused only a marginal spike: Threats like this would typically fan geopolitical tensions — and with them roil equity market volatility and commodity prices. However, if the movement in oil prices is anything to go by, that’s barely happening. In recent weeks, the oil market has already benefited from avoiding other geopolitical risks, such as possible attacks on Iran’s oilfields by Israel. Weak global demand coupled with a supply glut offers plausible explanation for oil’s depressed showing:  Oil’s march was further contained by Iran’s decision to stop increasing its stockpiles of uranium enriched up to 60%, as announced by the International Atomic Energy Agency. Why does this matter? ING’s strategists Warren Patterson and Ewa Manthey believe the move should remove some supply risks related to Iranian oil when President-elect Trump enters office. Ultimately, this should further restrain the commodity’s price.

Meanwhile, the International Energy Agency’s monthly oil market report forecasts a surplus of more than one million barrels per day, even if OPEC+ decides not to suspend its 2.2 million daily barrels of planned voluntary cuts: “However, much will also depend on compliance, given a handful of members have continuously produced above their target levels.” IEA expects non-OPEC+ producers to increase daily supply by around 1.5 million barrels in 2025, exceeding expected demand growth. Political risks to the natural gas supply in Europe as the winter heating season gathers steam are more unsettling. The crisis at the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war is a stark reminder of how dire the situation could get. Europe is now less dependent on Russian gas than two years ago, but the Netherlands’ natural gas benchmark price is steadily increasing, fueled by concerns that Russian pipeline flows to Europe face disruption: Heightened geopolitical tensions have prompted a flight to safety for a while, contributing to gold’s run this year — although it’s noticeable that the flurry of activity over Ukraine has had a minimal impact, with the metal down from its pre-election peak. The VIX, a standard way to hedge when risks look elevated, has shown continuing low volatility; investors may find the nuclear risk unhedgable. Bloomberg Intelligence’s Mike McGlone argues that gold’s run will resume unless there’s a significant downshift in tensions. The potential for a trade war is alarming. The risk of nuclear confrontation is of course far scarier, but as there’s no way to buy financial protection against it, it’s having less effect on markets. —Richard Abbey One UK institution not in need of any reform: Paddington the bear. I loved listening to the stories as a kid, and it’s been great to go with the family this week to see the third Paddington movie, which won’t hit the US until January. He travels to Peru, and a bunch of great actors have some fun; it’s charming and entertaining. It’s strange that nobody in Peru speaks Spanish; and no, it’s not quite as good as Paddington 2, in which Hugh Grant’s villain stole the show. But it’s still worth a viewing, or even a hard stare.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |