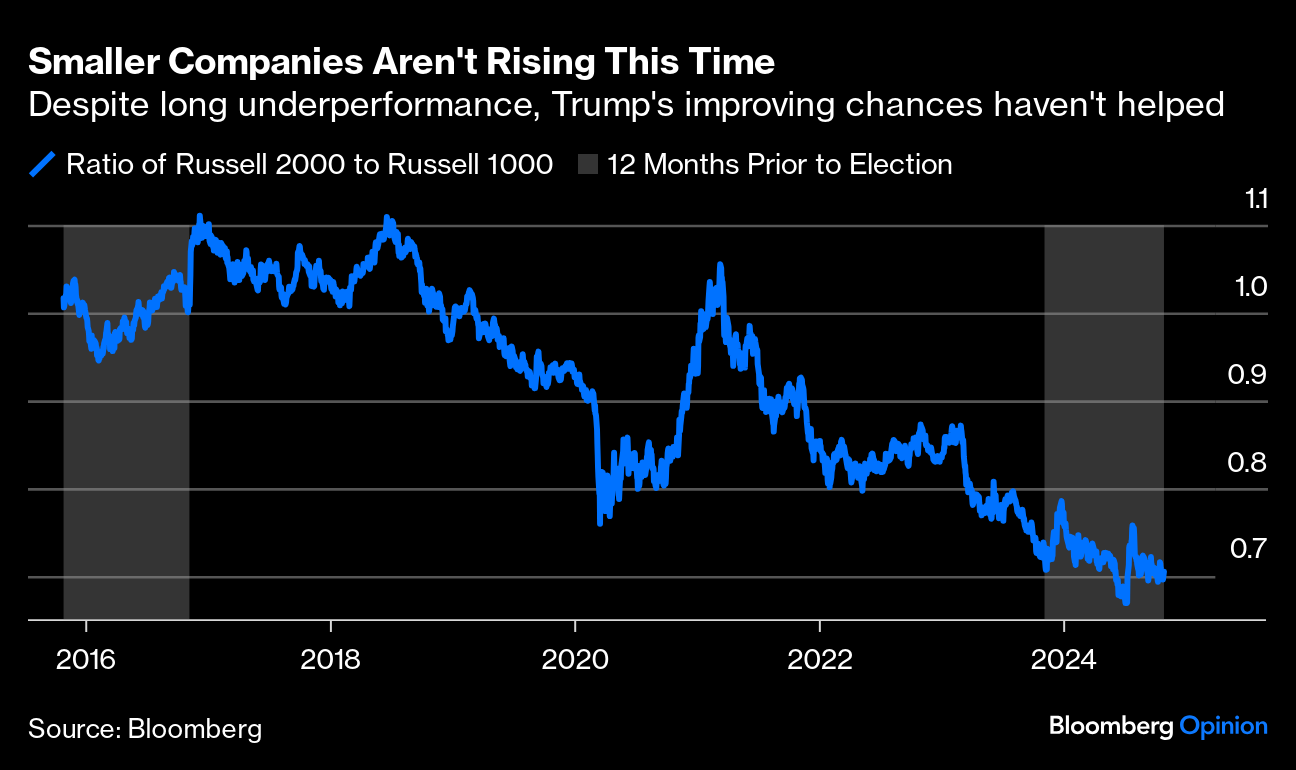

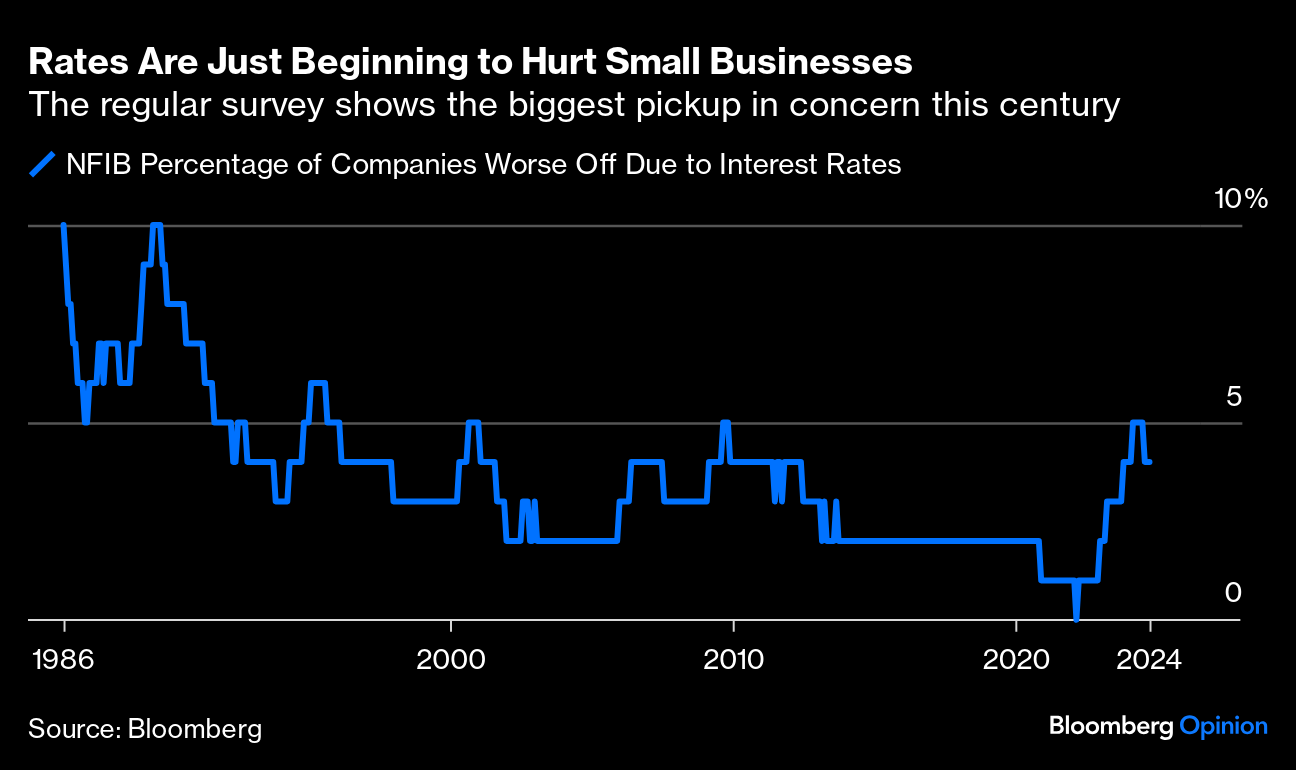

| The Trump trade is back in full sway, and many believe that we’re heading for a repeat of 2016. In other words, Donald Trump might well win next week’s presidential election, just as he did the one eight years ago. We’ll find out soon enough, but for the potential market consequences, there are some very important differences. First — and for this the predictions markets are genuinely useful — Trump's chances are now seen at about two in three, while eight years ago they were seen to be less than one in three. What happened in 2016 therefore came as a big surprise. There won’t be another this time. It also reflected extreme uncertainty about what a Trump presidency would entail. The experience of Trump 1.0 reduces that fear of the unknown. Even if there are good reasons to believe that a second term could be different from the first, the basic outline of what he plans to do is unchanged: tax cuts, deregulation, tariffs and an immigration clampdown. The difference lies in the context. Inflation had been under control for years in 2016, while rates had been anesthetized. That doesn’t apply this time. This is the 10-year Treasury yield in the two years before the last Trump victory, compared to the same yield over the last two years. The difference is obvious: Last time around, Trump’s arrival spurred a sharp rise in the yield, which soon found a plateau. It looks as though the bond market has tried to get that Election Day jump over with ahead of time in 2024. But the level is much higher, and it’s not so long since it touched 5%. A post-election rise in yields was survivable last time. In 2024, there’s much less room for maneuver. The protracted rally for stocks that went on for 15 months after Trump’s first victory is also unlikely to be repeated in full, partly because rates are higher now, while stocks start far more expensive. The S&P 500 was trading at about 1.8 times sales back then, and it’s now trading above three. This doesn’t mean that stocks can’t go on a decent rally, but it does tend to put a lower ceiling on one. The different rate position has also been reflected in the performance of smaller companies. Back in 2016, they had been outperforming nicely for much of the year, and then enjoyed a big surge after the election. This time, they’ve been lagging for years. There was an exciting reversal in their favor in midsummer, but that has petered out. Smaller companies haven’t joined in with the excitement over Trump’s improving odds at all:  Small caps look much more attractively cheap these days, of course, so there could be more of a deep value buying opportunity. But there’s something different about the way they’re behaving. The chances are that this is caused by interest rates. Smaller companies had less freedom to lock in low rates than their larger rivals, they tend to be more levered, and any rise in rates would begin to hurt. Mike Wilson, equity strategist at Morgan Stanley, points to an interesting nugget in the National Federation of Independent Business monthly survey of small business owners. The proportion who name interest rates as their biggest problem is still historically low, but it has jumped of late. This is one leg of a Trump trade that might not work this time around:  Then, there is the issue of tariffs. This is causing nerves in markets as a President Trump would have a relatively free hand to impose them, even without a GOP sweep of Congress (currently regarded by betting markets as roughly a 50/50 shot). But Deutsche Bank AG’s George Saravelos points out that a sweep would still strengthen his protectionist hand in one key respect: There is one element of trade policy that requires legislative approval: the withdrawal of China’s Most Favored Nation treatment under WTO rules. This would place Chinese imports under the punitive Smoot-Hawley Schedule II tariffs of around 50%. While we believe the same tariff changes could be achieved via executive authority, a legislative change would make this more permanent. We would expect the US to pursue this in the event of a Red Sweep given such legislation has already been submitted to Congress and has bipartisan support as expressed by this Congressional Committee.

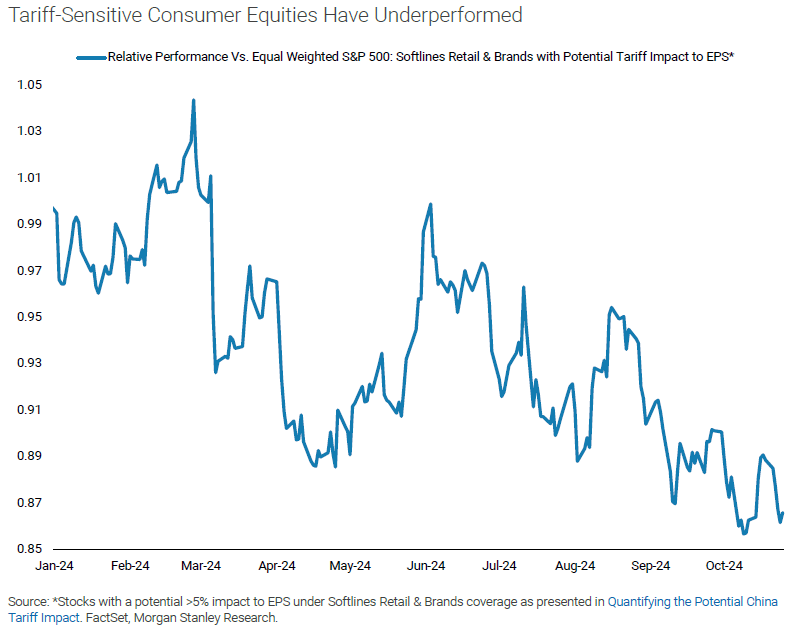

On this basis, it’s conceivable that all the bad news on trade for China isn’t yet in the price. However, it’s plain that share prices are moving on the assumption that tariffs will be rising. And that has led to another new development compared to 2016. Outside of Mexican stocks, which were perceived to be uniquely at risk in the outside chance of a Trump victory, the US campaign didn’t have much much global impact back then. In the last few months, however, the way that a range of large foreign markets have risen and fallen with the Democrats’ chances is spectacular. This dashboard shows how Japanese, German and UK markets all seem ultra-sensitive to PredictIt’s view of the election:  In the still extremely possible scenario that Harris wins, then the line in the top left-hand corner will shoot up to 100, and it’s fair to expect all the other lines to rise pretty significantly as well. If just because they would miss the numbing effects of Trump tariffs, this would be great news for European stocks. With less upward pressure on US rates, it would also strengthen the yen. That raises the question of where the burden of tariffs will fall. Trump himself generally denies that they’ll have any effect on the US consumer, which shouldn’t be taken too seriously. However, the way the pain is spread is subtler than it might appear. This is Saravelos again: Our read of the literature is that while the assessed short-run impact of the tariffs was largely borne by the US, it was mostly via lower retailer profit margins rather than US consumers. What is more, assessing the all-in effect on tax revenue and US production leads to a statistically insignificant effect of those tariffs in terms of economic cost. Critically, the upfront effects seem to wane over time, with the final impact shifting to China,

Again, note that Trump’s declared policy is to hike tariffs far more aggressively than the first time, which might change things. But this does suggest that retailers stand to bear the brunt of new tariffs. It’s plain that the market is wise to this and has moved accordingly. This chart from Wilson of Morgan Stanley shows how branded retailers who stand to suffer the biggest potential tariff impact have performed relative to the average stock. The smaller the company, the greater the effect:  This leads to a useful corollary. A Kamala Harris victory would at this point come as something of a surprise to the market — though not as big as the shock of 2016. That would mean no more juicy corporate tax cuts (although a Republican Congress could thwart outright hikes), and so would not be good for the stock market. If anyone stands to benefit from a Harris victory, it is those tariff-sensitive retailers who have already sold off. President Harris would help them outperform a likely declining market. It was the kind of report that seemed to need the Benny Hill theme tune in the background, but it’s actually quite important: Mentions of the word “bottom” have surged. As the earnings reporting season kicks into the highest gear, with five of the Magnificent Seven internet platforms due to report over the next three days, analysis by Bank of America Corp. of earnings call transcripts so far reveals that executives have grown far more willing to use language that suggests things will not get any worse. Its historical effectiveness as an indicator has been impressive: As ever, there is something strange about the bottom of this cycle compared with those that preceded it; it has come up when earnings are still increasing, and have been for more than a year. The return of animal spirits is evident. But this time around, it might make more sense to call it a signal of a “mid-cycle slowdown,” in jargon that used to be popular. Or in today’s argot, “no landing.” If you’d prefer to keep obsessing about the polls instead, there is yet another entrant into the frantic group of companies offering a chance to lose money on the election. Robinhood Markets Inc. is named after a mythical character who took from the rich and gave to the poor. The risk is that election betting might be more like Dennis Moore, and take from the poor to give to the rich. If that Monty Python humor is too much for you, then you could still channel your inner Benny Hill and watch for bottoms. Some more British humor, about America. My compatriot John Oliver’s latest take on his and my adopted country is utterly brilliant. Apparently, they played Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the USA” at his citizenship ceremony. (The USCIS was no longer doing that by the time I went to my own ceremony a couple of years later.) Oliver explains why, and offers an alternative involving Will Ferrell. The whole thing isn’t posted on YouTube yet, but it’s worth the wait, and you can find excerpts such as this one, which should be loved by Canadians. On which note, the first question in my citizenship test was, “Which country borders the USA to the north?” I got it right. Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Timothy O’Brien: Why Trump’s Presidential Campaign Came to New York

- Matthew Winkler: The Porterhouse at Weis Points to Inflation’s Demise

- Clive Crook: UK and EU Learn That to Divorce in Haste Is to Repent at Leisure

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |