| Other countries have elections too. And sometimes, voters make decisions that politicians and markets didn’t expect. Exhibit A for this is Japan, where the Liberal Democratic Party has just been deprived of a governing majority for the first time since 2009. It doesn’t matter as much to the rest of the world as next week’s US election probably will, but there will be consequences. The prime issue is that Japan is usually stable to a fault. Instability changes its offer completely. To quote Jesper Koll, the veteran investment banker who has been covering the country for decades and now publishes the Japan Optimist newsletter: In the world of money and investment, a key pillar to the “bullish Japan” thesis has been “Japan is a bastion of political and policy stability.” After today’s election, this will be more difficult to argue.

It’s a major surprise, as indeed was the election itself. Shigeru Ishiba took over as prime minister at the beginning of this month, following the resignation of Fumio Kishida, and called the vote to strengthen his position. It has done the opposite. Gearoid Reidy explains elsewhere in Opinion just how badly Ishiba, one of Japan’s most experienced and respected politicians, has bungled his first month in charge of Japan’s hegemonic party that has governed with only two interruptions since 1955. Interest in the election outside Japan was minimal, and almost no investors seemed prepared for a possible upset. But the next few years now look very different. When the LDP last lost power in 2009, Japan had three prime ministers from opposition parties in three years, and the mess unwittingly paved the way for the long supremacy of Shinzo Abe. The base case for the next few years is something similar, which is a big problem when the world looks more dangerous than 15 years ago, and Japan is trying to manage the transition away from decades of deflation. David Roche of Quantum Strategy in Singapore made this bearish assessment: What is sure is that policy uncertainty will rule while the haggling goes on. On a global scale, this is of course volatility in a teacup. But then Japan is a society that likes the calm of the tea ceremony. So, a storm in teacup matters to assets. I expect the yen to weaken. Equities will mark time (the bull period is over anyway). JGBs will stagnate waiting to learn about the next bout of futile fiscal largesse or lack of it.

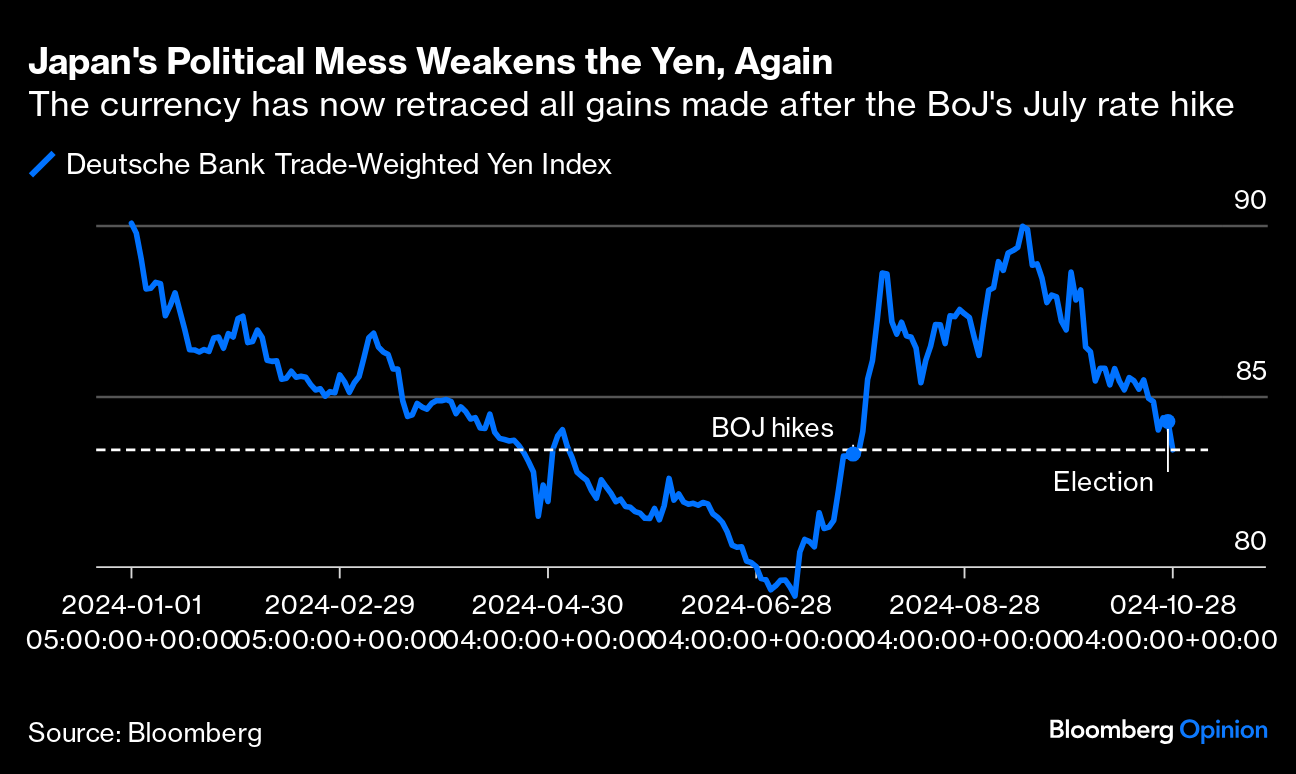

The yen remains important to the global system, and Japan’s descent into uncertainty might even prompt a return for the carry trade — borrowing in countries with low interest rates, such as the yen, and parking elsewhere to pocket the profit. The currency has now given up all its gains since the Bank of Japan hiked rates in late July:  Like the US, Japan will have a central bank monetary policy meeting within days of its election. Ishiba had already surprised observers by saying that the bank shouldn’t be too hawkish. Now, the initial reaction is that the political mess will make it harder for the Bank of Japan to be restrictive, even though part of the LDP’s problem was dissatisfaction with rising prices, which a generation of Japanese hasn’t known. That might provide more easy money for the rest of the world. The initial reaction in Tokyo suggests that the weak yen is as ever strengthening Japanese stocks. But the convulsions of early August as the carry trade unwound is a reminder than an unstable Japan is not good news for anyone. Another big event since markets last traded: Israel’s missile attacks on Iran. It wasn’t unexpected, but the reaction of the oil market in Asian trading has been a little counterintuitive. Crude prices dropped more than 5%. Israel opted not to attack the oil industry directly, a possibility once widely canvassed, and Iran swiftly confirmed that its production was unaffected. That continued a trend. This is how the price of Brent crude has moved in the last two years: Despite initial appearances, the short-term move downward makes sense. Not only was oil production unaffected, but both sides seem to lack appetite for another round of escalation. Peter Tchir of Academy Securities pointed to rival claims by Israel, who hope to have minimized Iran’s ability to deal with any future attacks, and Iran, which says the attack had little impact: At this stage, the outcome is likely not much different regardless of which side is telling the truth (or if the truth is somewhere in between), as neither side seems intent on escalating further. Yes, there have been some comments out of Iran calling for preparations for war, but does either side really want to escalate at the moment? Look for this to revert back to proxies and for oil prices to decline on the back of this controlled retaliation that is unlikely to provoke a direct response from Iran.

If the response to the latest round of hostilities makes sense, however, the broader message from the oil market seems totally discordant with many other current assumptions. Hard landing for the US economy is now thought highly unlikely, inflation breakevens have started to edge up again, and China has launched an attempted stimulus. A Trump victory would mean more tax cuts in the US, which should be expansionary. And yet the oil market is behaving as though demand is doomed. Eric Robertsen of Standard Chartered Plc puts it as follows: Oil is trading as if downside economic risks are all that matter and geopolitical risk is non-existent... Even with the escalation of military conflict in the Middle East, Brent oil has struggled to sustain prices above $80/barrel since Aug. 1. Furthermore, the oil market appears to be ignoring both recent signs of better-than-feared US economic activity and China’s significant stimulus announcements. In other words, oil is trading as if the macroeconomic backdrop has deteriorated over the last three months, while we would argue that the backdrop is marginally better than feared.

Early Monday’s sharp fall in response to the news from Iran suggests that there was indeed some political risk written into the oil price, and that it has now been removed. Traders’ perception of the economy was even weaker than it appeared. That ties in to the unavoidable topic of the moment. The Trump trade is alive and well, and not just in the prediction markets. Political betting has been around for centuries, and it’s been sporadically banned. The most compelling reason to do this, other than moral distaste for gambling, would be to limit the opportunities for political manipulation. All markets are prone to nefarious attempts to move them for financial gain, but could prediction markets be used to create a narrative, or be manipulated by those with inside information, on the election’s outcome? It’s certainly true that they have contributed to the growing narrative that Donald Trump will win the election next week. (Next week!) But it’s not so clear that they create any incentive or opportunity for dubious political activity that wasn’t there already. Koleman Strumpf, an economist at Wake Forest University who has studied the history of prediction markets, points out that political futures trading isn’t necessary to provide people with an incentive to try to change the results of the election: If there’s a way to change the outcome of the presidential election, then very simply I could find a basket of stocks and make billions of dollars. The incentives are there right now, regardless of whether there are prediction markets.

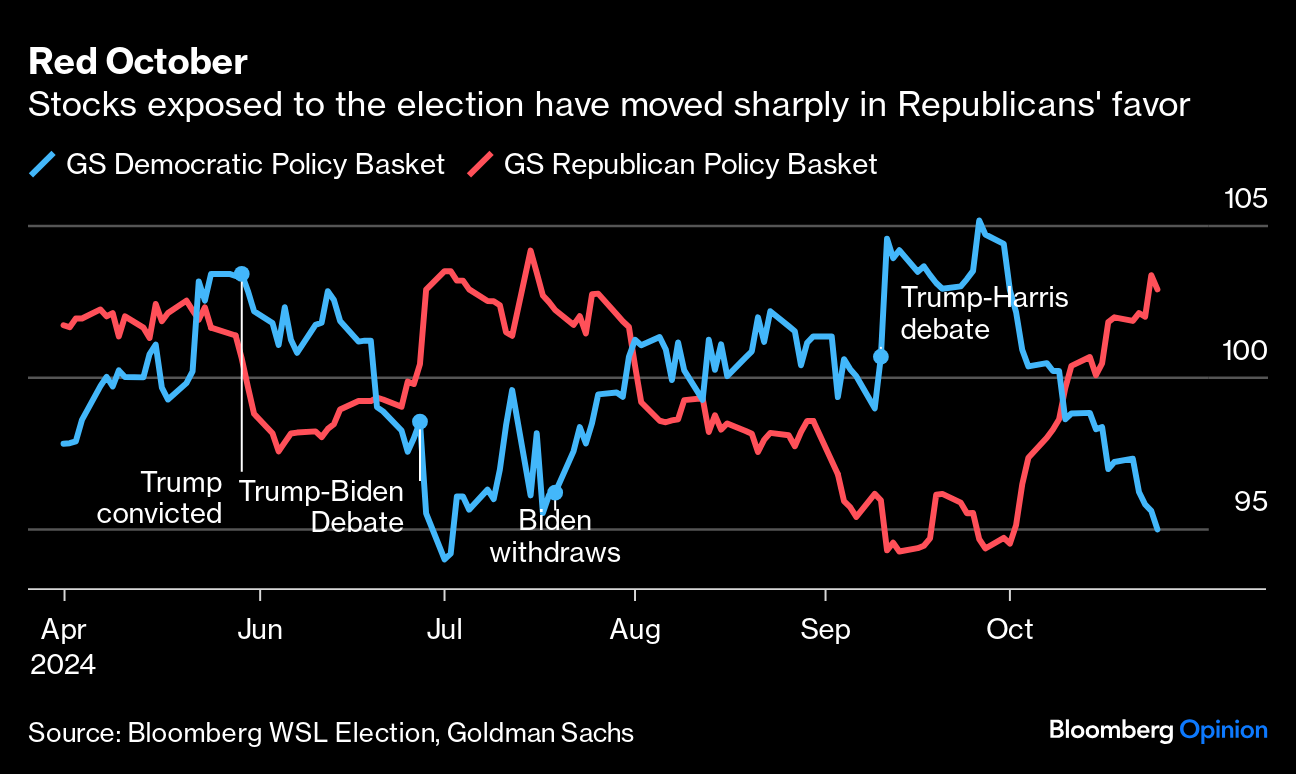

This isn’t just a thought experiment. Several investment houses have compiled such baskets of stocks that would be directly benefited or harmed by a victory for either party. Goldman Sachs’s policy baskets involved pairs — going long beneficiaries of the given party while betting against those that would do badly — based on the most direct impact of the party’s policies. The way those baskets have performed over the last six months is extremely reminiscent of the way that prediction markets themselves have moved. During October, despite no clear-cut news or events to change the course of the campaign, the Democratic basket has tanked and the Republican basket has surged:  Currencies are also moving to pre-empt a strong dollar under Trump 2.0, along with particular pain for economies that had hoped to benefit from near-shoring as companies moved production out of China. Japan, as we’ve seen, has had a number of shocks this year. The US currency rallied sharply against the Mexican peso after the surprisingly conclusive victory of Claudia Sheinbaum in June’s presidential elections. But the dollar has made strong gains against both the peso and the yen in the last month as traders have positioned for a Trump victory: Even the oil price can be construed as in part a reaction to the possible return of Trump. His one, oft-enunciated policy for dealing with inflation is to boost US oil production to push down energy prices. The market might be telling the Trump team that this needn’t be a priority, but an even bigger supply of oil hitting a world where demand doesn’t seem to be great wouldn’t be good for the price. As Robertsen of Standard Chartered puts it, there’s a “distinct lack of asymmetry” for anyone wanting to position in the dollar against the currencies that would most be harmed by a Trump return. The trades look as though they’ve already been put on, in the foreign exchange and stock markets (and of course the prediction markets). There’s not much more profit to be made.  Phil Lesh, Bill Kreutzmann, Jerry Garcia, Bob Weir, and Ron McKernan. Source: Bettmann/Getty Images Rest in Peace, Phil Lesh. The Grateful Dead bassist has passed away, 26 years after a liver transplant that allowed him to live into his 80s. As regular readers will have guessed, I’m not a huge Dead aficionado because I spent my formative years listening to the angrier young men of England’s punk and New Wave. But an advantage of writing this newsletter is that I’ve gotten to know plenty of Deadheads. So for examples of his virtuoso bass, let me recommend Viola Lee Blues live from Binghamton in 1970, Morning Dew, recorded live in Oklahoma in 1973, China Cat Sunflower, and Sugar Magnolia. Among the songs that he wrote or co-wrote were Box of Rain, about his dying father, with lyrics by Robert Hunter from 1970’s shimmering album American Beauty, Truckin’, Unbroken Chain and the countryish Pride of Cucamonga, and he was a force behind the classics St. Stephen and Dark Star. 1974’s Grateful Dead Movie has an unforgettable scene of Lesh talking about how many great tones his bass has. The film shows that Lesh was the pillar of the enterprise, even if Jerry Garcia was the animating genius. Another fascinating learning about Lesh is that he once studied music under Luciano Berio, the ultimate avant-garde modern composer. My Dad took me to see a performance of Berio’s Sinfonia when I was young, and I hadn’t a clue what to make of it, but it was exciting. Lesh felt much the same way, apparently, and Berio lives on in the Grateful Dead’s bass line. Be grateful for life while it’s here, everyone, and have a good week.

Like Bloomberg's Points of Return? Subscribe for unlimited access to trusted, data-based journalism in 120 countries around the world and gain expert analysis from exclusive daily newsletters, The Bloomberg Open and The Bloomberg Close. More From Bloomberg Opinion: - Marc Champion: Israel’s Strike on Iran Was Smart. Now Take the Win.

- Javier Blas: Oil’s War Premium Will Fade After Israel's Iran Strike

- Allison Schrager: The Art Market Needs a Restoration Project

Want more Bloomberg Opinion? OPIN <GO>. Or you can subscribe to our daily newsletter. |