| | In this edition, it’s time for tech to take up defense, and an OpenAI exec blames the users, not the͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ |

| |  | Technology |  |

| |

|

- OpenAI’s user problem

- AI fumbles ads

- Ex-Google exec strikes oil

- Social media safe space

- Trust in tech ticks down

OpenAI gives the military access to ChatGPT, and researchers decode an ancient Roman board game using AI. |

|

OpenAI’s decision to give the US military unfettered access to ChatGPT came after months of deliberation over whether employees would accept the deployment in the Pentagon’s new genai.mil program, which lets the agency use the AI models for unclassified purposes. A couple of factors made the company comfortable. First, unclassified workloads generally rule out a lot of combat use cases. Second, the same restrictions on ChatGPT’s consumer version will be applicable to the military version. So, if someone asked ChatGPT to help a user make a chemical weapon, the chatbot wouldn’t comply. OpenAI is breaking with competitor Anthropic, which, as you might remember from our scoop last month, set off Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth by asking for a say in how its AI models are used. The military said it wanted the software for “all lawful uses,” and the talks fell apart. The gulf between pro-military and anti-military is wider than the OpenAI–Anthropic divide. Lots of people in the tech world don’t want to speak publicly on the issue — there’s no real gain in doing so — but it’s an issue rankling everyone from top executives to AI researchers. Ahead of Trump’s second term, Silicon Valley’s libertarian and far-left factions discovered their patriotism after years of shunning work with the armed forces. They saw the political winds shifting and the rising threat from China and Taiwan — the biggest supplier of advanced semiconductors. The days when tech employees protested military work seemed long gone. But the capture of Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro, the Trump administration’s threats to invade Greenland, and ICE shootings of American citizens have started to make at least some vocal contingent of tech workers wary again. It’s not all of them. It might not even be the majority. But there’s an indication that something is changing. Defense tech will continue to be a hot area — there’s big money to be made and it often helps business to lend the Trump administration a hand. There’s also a real belief that the military needs the best technology possible, regardless of who won the last election. How Silicon Valley wrestles with these competing philosophies may be mostly an internal struggle right now, but it won’t be long before it bubbles up to the surface. And by the way, we just announced our first slate of speakers for the 2026 Annual Convening of Semafor World Economy, taking place April 13-17 in Washington, DC, with more than 400 top CEOs. Tech will be, as it is every year, the No. 1 topic of conversation as the business world grapples with how to adjust to an AI-driven economy, and how to get it to work inside their own companies. We have a bunch of interesting tech leaders, including Reid Hoffman and Anne Wojcicki. See the first lineup of speakers here. |

|

AI’s challenge is not the tech, but the user |

Ronnie Chatterji speaking at Semafor World Economy in 2025. Kris Tripplaar/Semafor. Ronnie Chatterji speaking at Semafor World Economy in 2025. Kris Tripplaar/Semafor.Blame the humans. AI hasn’t yet become the promised panacea for companies and their workers, but it’s not because the technology isn’t living up to expectations, according to OpenAI’s chief economist Ronnie Chatterji. It’s because workers aren’t using it correctly, he said. At a conference hosted this week by workplace-focused media company Charter, Chatterji described a Goldilocks problem where employees give AI tasks that are too small (using chatbots as a search engine) or too big (trying to solve billion-dollar problems). “There’s a difference between what our models can do and how people use them, and that’s the biggest story in AI in 2026 — closing that gap,” he said. It was a fascinating admission by one of the world’s largest AI companies, and one that may come back to bite the ChatGPT owner. The tech industry is littered with examples of companies that had superior technology but couldn’t master the art of getting widespread adoption (remember Palm Pilots? Betamax?). So many of these frontier AI companies have been so laser-focused on coming up with cutting-edge tech that only now are they coming around to understand they also need to make sure people use it. |

|

AI Super Bowl ads miss target |

Amazon Alexa/YouTube Amazon Alexa/YouTubeAI companies including Anthropic and Amazon faced some backlash for their Super Bowl ads, which critics say sent an “out of touch” message to consumers already skeptical of using AI. At the very least, the ads sold the wrong things, or messages (like how Amazon’s Ring can surveil neighborhoods), to the wrong people. Neither Amazon’s ads nor Anthropic’s, which jabbed at OpenAI, targeted their core AI user base. Meanwhile, OpenAI, the everyman’s chatbot company, advertised coding tools during the game, instead appealing to the tech-savvy crowd. In defense of the ads, one creative director argued they succeeded in educating the masses on AI. “It’s expectation-setting,” said Justin Barnes, executive creative director at production studio Versus. “Brands are signaling where the lines are, what behavior is acceptable, and what will never happen.” That kind of marketing — and the damage control that comes with it — only surfaces when products become familiar enough that advertisers don’t need to share technical explanations but personality and branding, he said. |

|

Ex-Google exec launches AI firm for refineries |

An oil refinery in California. Brittany Hosea-Small/Reuters. An oil refinery in California. Brittany Hosea-Small/Reuters.Sundar Pichai’s former chief of staff has started an AI company tailored to oil refineries and chemical plants, the latest bet that smaller upstarts can pick off specialized industries left behind by the tech giants, Semafor’s Rachyl Jones reports. Called Archimetis, the company analyzes data points from thousands of sensors, flags inefficiencies, and uses agents to offer up fixes. Like Cursor did for coding and Harvey did for law, Archimetis’ tool hopes to tap into the $1.7 trillion global market for refineries. For example, if the data indicates the equipment that performs heat transfers is lagging, it can flag “gunk” built up in the machine and suggest what could have caused the build-up — something that would take engineers “hours,” said Cofounder Paul Manwell, who worked at Google for 14 years before striking out on his own. |

|

Semafor is proud to announce its first slate of speakers for the 2026 Annual Convening of Semafor World Economy, taking place April 13-17 in Washington, DC. This global cohort of senior leaders from every major sector across the G20 are just some of the 400 top CEOs joining Semafor World Economy for five days of onstage conversations and in-depth interviews on growth, geopolitics, and technology. See the first lineup of speakers here.

|

|

Meta and Google social platforms under trial |

Evelyn Hockstein/File Photo/Reuters Evelyn Hockstein/File Photo/ReutersA high-profile trial against Meta and Google began in Los Angeles this week, testing claims that the social media platforms are designed to be addictive. The question has plagued regulators for more than a decade, with social media addiction cited in connection with increased anxiety, body image issues, suicidal ideation, and poor mental health in adolescents. Now that Australia has banned social media for individuals younger than 16, it is the largest real-world test case for how the platforms directly impact the mental health of minors. If the harms laid out by politicians and academics for a decade are as severe and widespread as claimed, we should start to see some real results. But so far, there haven’t been a ton of formal studies on the issue. There are some new surveys, but based on a review of projects that have been announced, most appear to be limited in scope, and few organizations outside the country are participating. There’s a real opportunity here to figure out one of tech’s biggest problems — technologists and researchers just need to start taking advantage of it. |

|

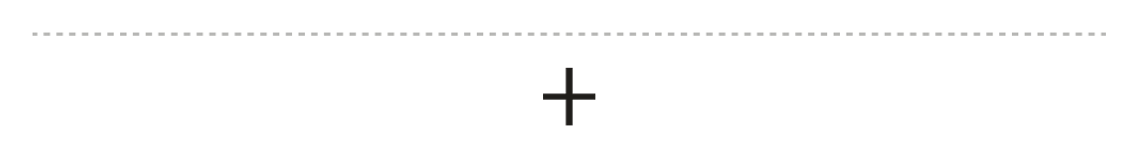

Trust in tech drops globally |

Trust busting. Edelman’s latest “Trust Barometer” report, shared exclusively with Semafor, measured a 3 percentage point global drop in users’ trust in technology companies going into 2026, compared to the previous year. Researchers say trust in systems drives adoption, while distrust serves as a barrier to the systems’ development. China is among the few countries where respondents indicated more trust in tech year over year — a symptom of a country in which information is tightly controlled and the press is limited — while the US hovers around 30 percentage points lower. The difference is even starker when measuring trust in AI companies specifically. Trust fell globally across nearly every institution, including education, health care, and financial services. The only business category that saw a year-over-year increase, unexpectedly, is social media, though it still holds the lowest overall trust score. |

|

Everyone talks about AI. Mindstream helps you actually get it. Join 220,000+ folks who depend on this free daily newsletter for the sharpest informed takes, latest breakthroughs, and tools you’ll actually use. While others are overwhelmed, you’ll be out front. Subscribe today. |

|

Restaura/Crist W, Piette É, Jeneson K, et al. Ludus Coriovalli: using artificial intelligence-driven simulations to identify rules for an ancient board game. Antiquity. 2026;100. Restaura/Crist W, Piette É, Jeneson K, et al. Ludus Coriovalli: using artificial intelligence-driven simulations to identify rules for an ancient board game. Antiquity. 2026;100.The rules of an ancient Roman board game may have been decoded by AI. The stone tablet with an etched hexagonal playing area was discovered in the Netherlands around a century ago. Researchers used AI agents to play thousands of games using 100 different ancient and modern rulesets, and compared results to the levels of wear on the board. It was likely a “blocking” game, with players trying to prevent each other’s moves — imagine tic-tac-toe but more sophisticated — and is the earliest known example of such a game, Scientific American reported. It’s not AI’s first archaeological outing: It was used to decipher papyrus scrolls burned in the eruption of Vesuvius, and discover hitherto unknown structures in Peru’s Nazca lines. — Tom Chivers |

|

|