|

Why America's extremes will both fail

The right narrows its coalition, while the left parasitizes its patrons

These days it seems like the only things to write about are politics and AI. I wrote about AI last time, so today I’ll write about politics.

Here is my basic theory of American politics in the 2020s: The United States is a nation of moderates ruled by a fringe of extremists. The extremists rule because they are more engaged than the moderates — they spend more time thinking about politics and doing political activism. In Martin Gurri’s terms, the extremists are the “public” and the moderates are the “populace”.

There are several reasons why American politics is dominated by extremists. The well-known one is the closed-primary party system. Republicans win primaries not by aligning with the median voter, but by aligning with the median Republican voter — usually in an area that’s already right-leaning to begin with. The same is true of Democrats.

But that has been true for a while. The fundamental reason why American politics is more extremist-dominated than in the past is technological. Modern social media bypasses traditional hierarchies and institutions and gathers together communities of like-minded extremists who then create challenges to traditional institutions; it also provides these extremists a platform in which their emotionally charged messages are more likely to go viral than messages of positivity and reason.

The moderate majority increasingly avoids the politically charged, extremist-dominated online spaces. That gives lots of Americans more peace of mind, but it also means that online spaces become more and more extremist as moderates leave.¹ This is the conclusion of Törnberg (2025):

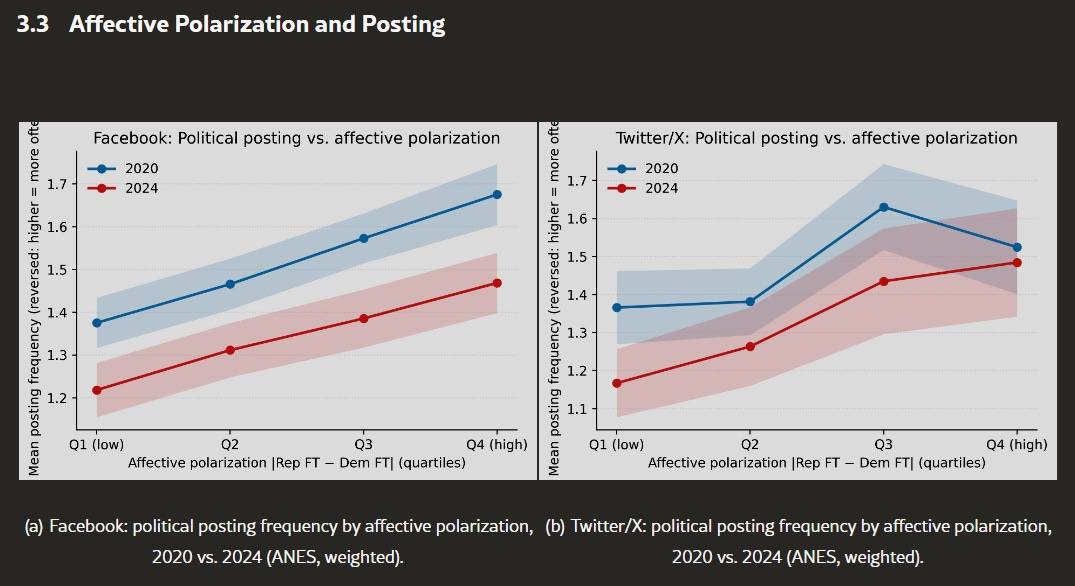

Using nationally representative data from the 2020 and 2024 American National Election Studies (ANES), this paper traces how the U.S. social media landscape has shifted…Overall platform use has declined, with the youngest and oldest Americans increasingly abstaining from social media altogether. Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter/X have lost ground, while TikTok and Reddit have grown modestly, reflecting a more fragmented digital public sphere….Across platforms, political posting remains tightly linked to affective polarization, as the most partisan users are also the most active. As casual users disengage and polarized partisans remain vocal, the online public sphere grows smaller, sharper, and more ideologically extreme. [emphasis mine]

In case you like charts, here’s one from the paper showing that extremists post more than moderates:

|

If extremists remained online, shouting at each other or shouting into the void, this would be a good and healthy process for a nation weary of culture wars. But the people who dominate real-world politics are increasingly drawn from this pool of online extremists. I am talking not about elected politicians themselves, but about the activists who create and promulgate political ideologies, the think tankers who translate those ideologies into policy ideas, the lobbyists who promote those policy ideas to politicians, and the staffers politicians hire to decide which ideas to embrace, and how.

Let’s talk about those staffers for a moment. Staffers write legislation, advise elected officials on policy, and handle lots of public communications. While politicians are out fundraising, pressing the flesh, or giving speeches to increasingly outdated TV news networks, their staffers are busy with the business of running the country. These staffers are much younger than the politicians they ostensibly serve — the typical Congressional staffer is in their late 20s, while the typical Congressperson is in their late 50s.

This means staffers are more online, and thus spend their days lost in the extremist maelstrom of social media, mainlining rightist conspiracy theories on X and leftist tropes on TikTok. Staffers are also unelected, which means they don’t have to cater to regular voters; they are free to pursue radical ideologies, support radical movements, and put out extremist messaging unless their bosses explicitly act to rein them in.² There are plenty of anecdotes about how staffers in both the Democratic Party and the Republican Party are more extremist than the politicians they serve — to say nothing of the country as a whole.

For a concrete example of this, take the recent contretemps over one of Donald Trump’s racist social media posts. Trump’s Truth Social account posted a video depicting Barack and Michelle Obama as apes:

After a general outcry, the racist video was taken down. A White House official stated — and