| | In today’s edition: Gulf ambition stirs Wall St. rivalries, expats export cash out of Saudi Arabia, ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ |

| |   New York New York |   Muscat Muscat |   Abu Dhabi Abu Dhabi |

| | | Global Capital Edition |

| |

|

- Clash of titans

- Saudi expats’ chief export

- Vision 2030 drives credit

- Muscat’s glowup

- Crowning a financial hub

Competition with China, and a room with a view in the Jabal Al Hamri mountains. |

|

It has been impossible to ignore the ambitions of Gulf states aiming to become linchpins in the global AI arms race. Saudi Arabia has said it wants to be the third-biggest global compute hub, after the US and China. Abu Dhabi-controlled funds have poured billions into partnerships with Microsoft and BlackRock, and Qatar has invested in AI firms Anthropic and xAI. Each country has created its own AI champion. Clearly, Gulf leaders see AI as a revolutionary technology that will reshape the world economy — much like their peers the world over. But in conversations with senior figures in the Gulf, I’ve noticed another, less remarked upon, tectonic shift underway that they anticipate, and which they are starting to mobilize their vast sovereign funds to monetize: entertainment. In their techno-optimist view, AI revolutionizes our lives: Workers become more productive and richer, the working week gets shorter, and we all get healthier and live longer. That will leave us with more leisure time — and more money to spend enjoying ourselves. Emirati, Qatari, and Saudi funds joining forces to back Paramount Skydance’s $108 billion hostile takeover offer for Warner Bros. Discovery wasn’t just a rare display of cooperation in a region more characterized by economic competition — it was the biggest display of their willingness to put their financial resources behind this investment thesis. A similar strategy lies behind Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund leading the more than $50 billion buyout of Electronic Arts, a deal that shocked many Saudi watchers who thought the sovereign wealth fund was lowering spending. But as that deal showed, conviction in the region is high that the next wave of giant companies, maybe even trillion-dollar firms, will not come from energy or technology, but from media and entertainment. |

|

Gulf ambitions stir Wall St. rivalries |

Hamad I Mohammed/Reuters Hamad I Mohammed/ReutersA plan by ADNOC’s investment arm and Apollo to pour billions of dollars into AI died this autumn in the boardroom of Apollo’s biggest Wall Street rival. The asset management giant had been drawing up plans for a new fund with Abu Dhabi’s XRG, initially targeting about $5 billion, focused on global AI infrastructure, people familiar with the matter said. XRG’s board met to discuss the project at the New York offices of Blackstone, whose president, Jon Gray, is an XRG board member. Gray voiced concerns — ultimately echoed by other directors — that the project went beyond XRG’s mandate as an operator of energy and chemical assets, the people said. The plans were scrapped, leaving some Apollo executives believing a rival had torpedoed the deal out of jealousy. XRG, Blackstone, and Apollo declined to comment. The failed plan offered a glimpse of how intense rivalries, in the Gulf and on Wall Street, are shaping a moment when investors see huge returns in helping the region turbocharge its economic transition from oil to tech. While bankers have learned to balance the interests of the UAE, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar — each keen to be a regional hub for high finance — Gulf leaders are learning that their Western partners also have their own politics. |

|

Expat hiring boom sees Saudi remittances surge |

Saudi Arabia may no longer be the exporter of capital into global financial markets that it once was, but in at least one area the amount of money leaving the country has soared: As the kingdom’s foreign workforce has swelled, outbound remittances have risen to the highest levels on record, government figures show, leading to a surge in cash leaving the Saudi economy as expats send earnings home. Remittances by expatriates amounted to nearly $14 billion in the second quarter of the year, the most recent data available shows — an increase of about 50% since 2017. That’s also a reflection of the country’s surging numbers of foreign workers: Since 2017, around 1 million jobs have been created for Saudis, compared to 1.4 million jobs for expatriates. The kingdom has been working to stop what it calls “leakage” of money outside the country by both citizens and expatriates by loosening social restrictions and improving quality of life via culture and entertainment. But it is yet to go as far as neighboring UAE, which has already made property investment widely available to expatriates and also established retirement saving products to encourage foreign workers to keep their cash inside the country for the long term. — Matthew Martin |

|

Private credit: small but mighty in the Gulf |

Hamad I Mohammed/Reuters Hamad I Mohammed/ReutersOne of the world’s fastest-growing asset classes is gaining steam among Gulf sovereign wealth funds and family offices — and is an emerging lifeline for Saudi Arabia. Private credit allocations from Middle Eastern family offices have steadily increased from negligible in 2021 to around 2% of portfolios, picking up in 2022 when an end to zero-interest rate policies among central banks and slowing public markets began to push borrowers toward nonbank lenders. The Gulf’s state-backed investors have followed, with Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Mubadala, and the Qatar Investment Authority among those building multibillion-dollar private credit platforms. Saudi Arabia, by contrast, stands out for its domestic borrowing, according to S&P Global Ratings. While private credit still represents just around 2% of Saudi Arabia’s total debt — “nothing,” according to the head of the country’s capital markets regulator — the asset class has grown tenfold since 2020 to roughly $3.7 billion, according to the ratings agency. Vision 2030’s massive funding needs, particularly the emphasis on small-business owners increasing their contribution to the kingdom’s economy, is expected to drive continued demand. — Kelsey Warner |

|

Muscat’s model fiscal behavior |

Oman Ministry of Information/Handout via Reuters Oman Ministry of Information/Handout via ReutersA little over a year ago, Oman was classified as a junk bond issuer by all three major ratings agencies, but all have changed their position, amid what looks like — from an investor perspective — model behavior by Muscat. Standard & Poor’s (S&P) broke from the crowd in Sept. 2024, with an upgrade to move the country above the investment grade threshold; Moody’s followed in July this year, and Fitch Ratings added the final piece in the jigsaw this month. The common theme across the upgrades has been Oman’s success in reducing its debts and budget deficits, despite subdued oil prices and voluntary cuts to crude output alongside OPEC members (Oman itself is not a member of the cartel). Spending has been kept under control and the government has been willing to take political risks, too: The region’s first income tax is due to be levied on Oman’s high earners in 2028. The big underlying factor is the reform program launched by the country’s ruler, Sultan Haitham Al-Said, after he took power in January 2020. Omani officials have largely stuck to their pledges of prudence, albeit with some delays. That is in contrast to Bahrain, another small Gulf economy with a history of fiscal difficulties, where reform efforts have stalled; Bahrain was downgraded again in November by S&P and is deep in junk bond status. |

|

A new read on financial clout |

Abu Dhabi’s global rank among top financial centers. NYU Abu Dhabi’s Stern School of Business placed Abu Dhabi ahead of Dubai (14th), Riyadh (26th), and Doha (29th) in an index of competitiveness among financial centers. The ranking is based on the scale and institutional heft of a given city’s roster of firms, and the potential for growth and innovation. Its creators want the index to guide strategy and show how quickly newer hubs can move when public policy, talent, and capital align. Competition among regional capitals to emerge as an international finance hub is still intense, with no city yet managing to take the crown. “Somewhere between Europe and Asia there’s room for a new financial center addressing an economic area of East Africa, North Africa, all the way through the Gulf, Turkey and India,” the president of Singapore’s stock exchange group SGX, Michael Syn, told Semafor. “But no single hub has emerged as an obvious champion.” |

|

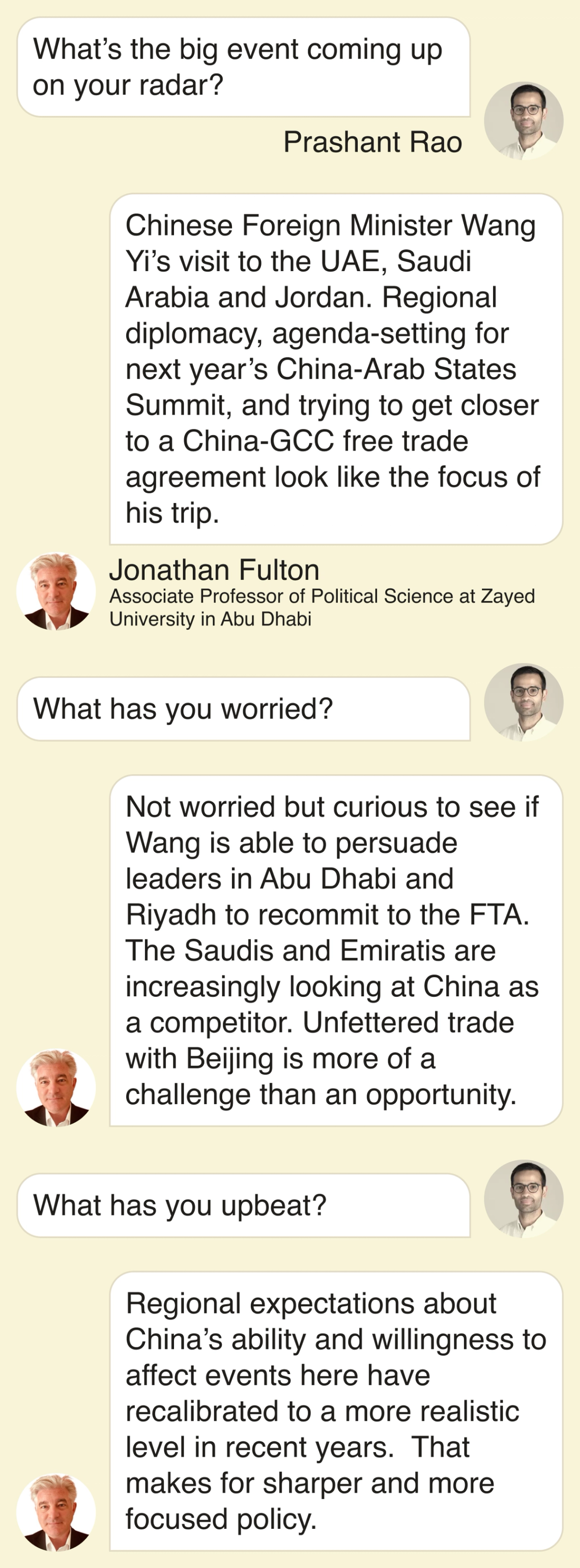

Every week, we ask a different expert what they’re focused on. Today, we’re talking to Jonathan Fulton, associate professor of political science at Zayed University in Abu Dhabi.  |

|

Courtesy of Parvara Courtesy of ParvaraFor travelers unmoved by the glitz of palace hotels in capital cities, Gulf hoteliers are offering up something new. Parvara, a mountain retreat in the northern emirate of Fujairah, opened in late November and offers screen-free stays built around fixed itineraries. Guests stay in stone pavilions and choose a theme like a digital detox or a solo stay, with firelit dinners and stargazing. The property is part of a broader tourism push in the Gulf where stripped-back, rugged luxury is increasingly part of the region’s brand. Oman’s Anantara Al Jabal Akhdar resort sits high above a canyon two hours from Muscat. In Saudi Arabia, places like Habitas and Banyan Tree in AlUla, home to UNESCO World Heritage Sites, show another side to the Gulf, and for around $1,000 a night, you, too, can book off the beaten path. |

|

|