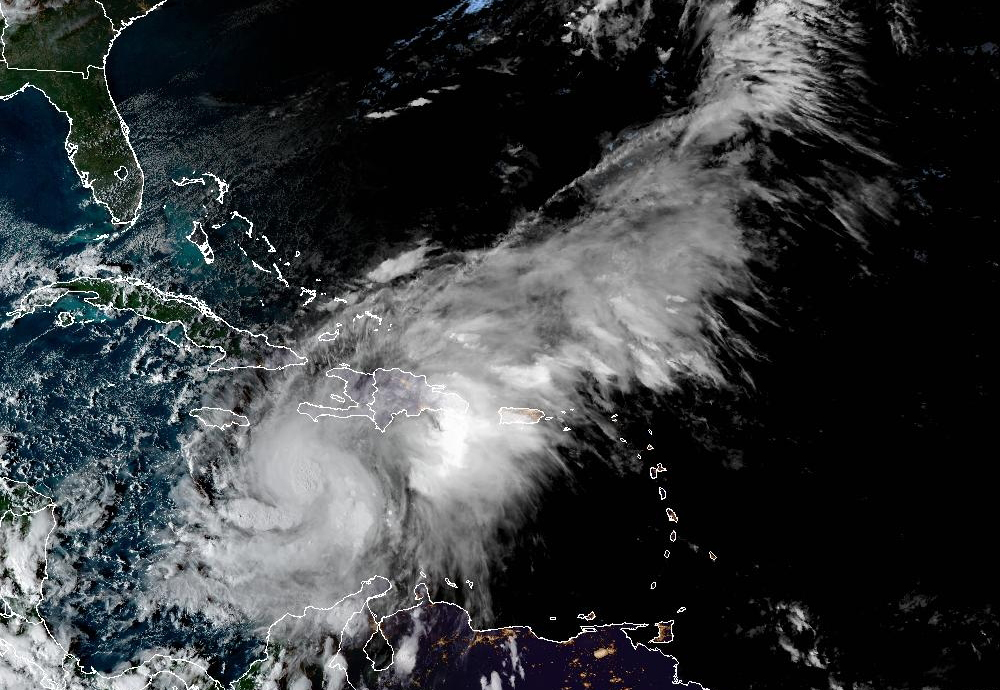

| By Lauren Rosenthal  A satellite view of then-Tropical Storm Melissa on Friday. NOAA For days, Storm Melissa has barely budged. It portends potentially catastrophic flooding for parts of the Caribbean as soon as this weekend. Melissa is projected to morph into a Category 4 hurricane — one notch below the highest level — while lingering off the coasts of Jamaica and Haiti. The risk is clear: a storm akin to Hurricane Harvey, which produced deadly flooding when it stalled over Houston in 2017. Melissa’s rains have already begun, and over the next few days, the storm is expected to drop several feet of water onto increasingly soggy mountainous terrain. As the days tick by and Melissa’s winds pick up, experts say, the likelihood increases that mountainsides could give way, carrying deluges of mud, trees and even structures into populated valleys and foothills. “I just can’t see how this avoids being a humanitarian disaster,” says Chuck Watson, a scientist with disaster modeling firm Enki Research. The storm has come to a near-halt over an area where ocean waters are expected to reach 88F (31C), with ample stores of heat well below the sea surface. If the storm were to pick up forward momentum, it might churn up colder water that could hamstring its growth. But the longer Melissa sits, says Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, the more opportunity it has to pull energy from the surrounding Caribbean waters, raising the potential for the storm’s winds to rapidly intensify. “All hurricanes do is go with the flow,” McNoldy says. “If there isn’t flow, they don’t go.” Officials in the Caribbean have begun alerting the more than 1 million people living in mountain valleys along the storm’s projected path, opening emergency shelters and preparing residents to evacuate in a hurry if needed. In a post to X on Wednesday, Haiti’s civil defense office asked people to stay out of rising floodwaters and look out for neighbors as Melissa approaches. “Show solidarity with the weakest: the elderly, people with physical disabilities and children,” the ministry wrote. The economic toll from Melissa is expected to be severe. Depending on how the storm progresses, financial losses in Jamaica alone could reach $3 billion, Watson says. “That would be the equivalent of a multi-trillion-dollar storm in the United States—trillion with a ‘T,’” Watson says of the storm. Read the full story and track Melissa’s latest moves on bloomberg.com.  A Stargate AI data center under construction in Lordstown, Ohio. Photographer: Kyle Grillot/Bloomberg From trade wars to skyrocketing tech valuations, governments and investors seem to be making economically irrational moves. As the world heads into another global climate summit, there is a need for fresh thinking to bring countries back to work on the urgent challenge of climate change. This week on Zero, political economist Abby Innes tells Akshat Rathi what governments are getting wrong about addressing the problems we face and how to reimagine economics for the climate era. Listen now, and subscribe on Apple, Spotify or YouTube to get new episodes of Zero every Thursday. Disaster recovery is an increasingly big business. Our Eric Roston traveled to Asheville, North Carolina, which was devastated by Hurricane Helene last year. He went to see how recovery was going and trace the nearly invisible supply chains that allow places struck by tragedy like Asheville to recover — and how the companies that are part of them are driving the economy. Below is an excerpt from Eric’s piece, which is the first installment in our new series we’re calling Disaster Industrial Complex. Please subscribe to Bloomberg News to catch future stories in the series.  Completely destroyed artist galleries and studios in the River Arts District. Photographer: Mike Belleme/Bloomberg Weather disasters like Helene are becoming both more frequent and more severe because of climate change. Although they blow over fast in physical terms, the economic impacts play out slowly. It takes three to six months for survivors’ insurance checks to land, at best; maybe three years for federal reimbursements to cash-strapped localities to drip out. The result is that the US is now always paying to recover from disasters, and this is contributing a larger and larger share of GDP growth. The US economy has grown by $20 trillion since 2000, to $29 trillion last year. About $7.7 trillion of that — or 36% of all the growth in GDP — is spending related to recovering from or preparing for disasters, according to research by Andrew John Stevenson, a senior analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “It is undeniable now that climate change is having significant effects on the drivers of the economy,” says Sarah Bloom Raskin, a professor at Duke Law School and former deputy treasury secretary in the Obama administration. “You don’t have to squint hard to see that extreme weather events are so harsh and strong, and so repeated, that they are affecting labor-market functioning, supply chains, insurance markets and inflation dynamics in ways that are pronounced, prolonged and pervasive.” The country spent almost $1 trillion in the 12 months ending in June, money that most everyone would prefer to spend on goods or services of their choosing. In the 1990s, the annual average was closer to $80 billion in current dollars. Government spending on disasters, and companies leading the recovery, make up an underappreciated, yet major, slice of the US economy. The money goes to insurers and waste haulers, power grid equipment manufacturers and engineering contractors, hardware stores and self-storage facilities. These are good businesses to be in in challenging times. Stevenson created a set of about 100 large public companies across many sectors that together outperformed the S&P 500 by 6.5% a year from October 2015 to October 2025. He calls it the Prepare and Repair Index. “This is a growing part of our economy, and we don’t treat it that way,” he says. Companies in the index aren’t generally explicit about their role in disaster preparation and recovery, and they usually have other lines of business as well. The group is the top of a pyramid of countless smaller, private companies around the US like roofing contractors and mold remediators. But the index companies (shown here in green) are aware that disasters affect their bottom line. For Lowe’s Companies Inc., to take one example, “storm-related demand from hurricanes Helene and Milton drove better-than-expected results,” Chief Financial Officer Brandon Sink said on an earnings call in February. Hurricane-related demand buoyed fourth-quarter sales, he said, “as homeowners began the shift from securing their properties and cleanup towards recovery and rebuilding.” The term “climate adaptation” evokes highly planned, top-down efforts to build seawalls around cities or protect food crops from drought. But on the ground, adaptation is often smaller and scrappier — like installing a backup sump pump in your basement. Read the full story, including how the Trump administration’s actions could impact the disaster industrial complex. Reader’s favorite stories this week |

|