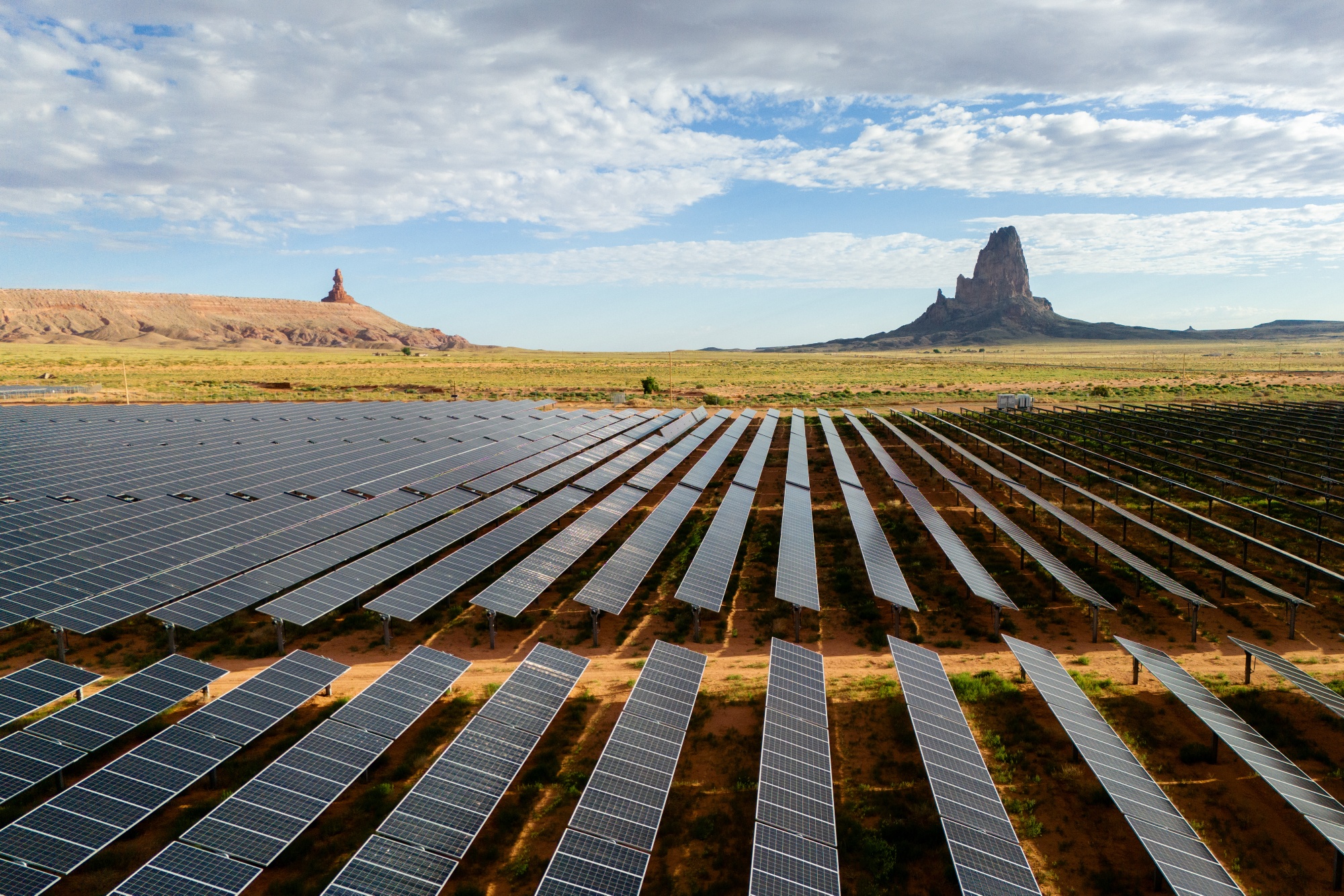

| By Emma Court and Olivia Raimonde If any nonprofit epitomizes the whiplash experienced by climate advocacy groups in the US over the past few years, it’s Rewiring America. Founded in 2020 shortly before former President Joe Biden was elected, the organization focuses on shifting US homes from fossil fuel-powered appliances to electric ones like heat pumps — a prime goal of Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act when it was passed in 2022. Rewiring America was poised to receive nearly $500 million from a $27 billion program created by that law. In February, the group was blocked from accessing those funds, and the Environmental Protection Agency, which administers the program, has since terminated $20 billion in grants because of “substantial concerns” about “program integrity, the award process, programmatic fraud, waste, and abuse, and misalignment with [the] agency’s priorities.” The program is under investigation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, according to the agency. Meanwhile, grantees have sued over frozen bank accounts. The funding uncertainty put Rewiring America in a bind, says Chief Executive Officer Ari Matusiak, “and so we had to make the decision to operate financially as though the dollars weren’t there.”  A solar plant overseen by a nonprofit organization in Kayenta, Arizona. Photographer: Brandon Bell/Getty Images It’s led to Rewiring America laying off 36 staff — more than a quarter of the organization — and scaling back its work while putting more focus on regional projects. President Donald Trump’s assault on clean energy regulations and funding has hit other parts of the climate NGO sector. Biden-era programs that injected billions into nonprofits have been culled, and leading philanthropists have warned they’ll be unable to fill in the gap. At risk is the energy transition in the US as nonprofits struggle to provide services while also playing defense to protect remaining federal climate programs. “We still need to act now to stop some of the worst impacts of climate change,” says Randall Kempner, founder and executive director of the Climate Philanthropy Catalyst Coalition. “That fact has not changed. If anything, our ability to move on that has been negatively impacted by the change in the administration and its policies.” Rewiring America isn’t alone: US climate-related nonprofits have cut positions and looked for other ways to cut costs in recent months as the flow of funds has dried up. Environmental group RMI has also cut jobs, laying off about 10% of its staff in May following federal funding cuts. The New Orleans-based nonprofit Deep South Center for Environmental Justice had to lay off eight staffers after losing a $13 million, five-year federal grant in February, says Beverly Wright, the group’s founder and executive director. “We hired a lot of people we had to let go,” Wright says. “I thank God we hadn’t hired even more.” Nonprofits were among the entities eligible for around $54 billion of the IRA’s nearly $105 billion in climate grants and direct agency spending, according to the Inflation Reduction Act Tracker, a project run by Columbia Law School and the Environmental Defense Fund. The White House didn’t respond to specific questions about the effect of cuts on nonprofits. Spokesperson Taylor Rogers says the tax law Trump recently signed “will create thousands of good, new, good-paying jobs thanks to the explosive growth” it will bring.  A worker installs no-cost solar panels on the rooftop of a low-income household in Pomona, California. Photographer: Mario Tama/Getty Images Some foundations are increasing their giving or easing administrative processes for grantees. But “there are definitely going to be some foundations who do not want to run afoul of the Trump administration,” says Kempner, the founder and executive director of the Climate Philanthropy Catalyst Coalition, given its attacks on “private-sector organizations with whom it disagrees.” Large institutional foundations are most likely to increase their grantmaking, says Kempner, whose coalition is composed of philanthropic networks, advisory firms and foundations. Corporate giving has also continued, he says, but organizations aren’t talking about it as much or are shifting how they describe their climate programs, part of a phenomenon known as greenhushing. “There’s no way that philanthropy over the next two or three or four years can fill in where the federal government has pulled back,” Kresge Foundation President and CEO Rip Rapson says. “A foundation like Kresge is a mid-sized foundation, and yet we could deplete our annual grantmaking easily with just a handful of grants to people who are in vulnerable positions.” Read the full story on Bloomberg.com — and subscribe for more reporting. |