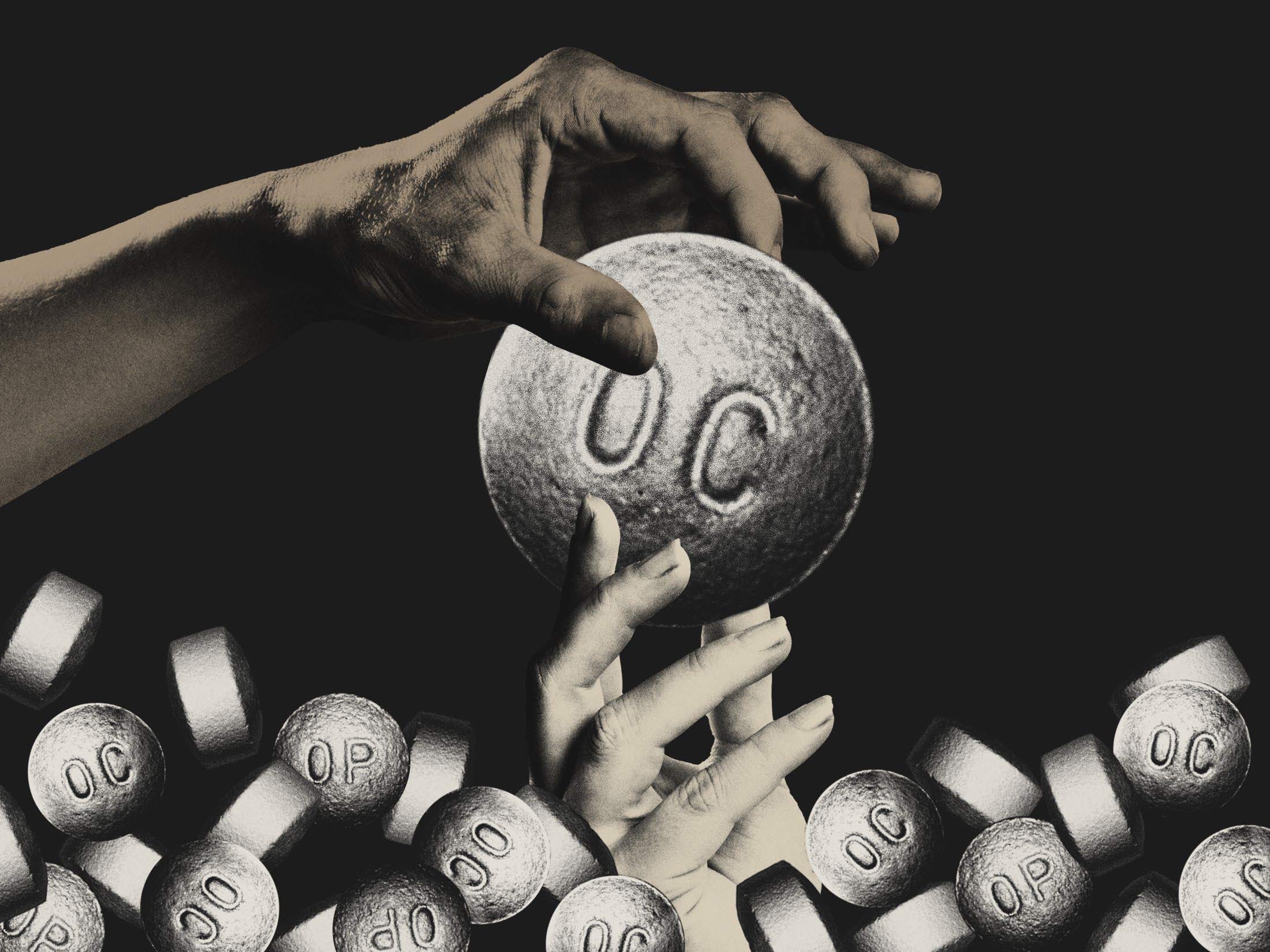

| Earlier this year, Sam Hornblower wrote for Bloomberg Businessweek about the FDA’s role in igniting the opioid epidemic. That article is back in the news, and today in collaboration with the Prognosis newsletter we’re publishing his explanation why. Plus: Companies retreat from their environmental goals, and nicotine pouches are bedazzled for a new market. Help us improve Bloomberg newsletters: Take a quick survey to share your thoughts on your signup experience and what you’d like to see in the future. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. FDA Commissioner Marty Makary laid out his priorities for the agency in a piece published in JAMA Network Open on June 10. He promised to take conflict-of-interest issues seriously, writing that the agency “will never forget one of the worst self-inflicted wounds of US health care—the Food and Drug Administration’s illegal approval of OxyContin for chronic pain based on a 14-day study.” It marked the first time the agency has said this was an “illegal approval.” In doing so, Makary added a footnote that linked to my article from April. My story in Businessweek and our Wall Street Week piece traced FDA decisions on Purdue Pharma’s OxyContin and other opioids that broke with scientific and regulatory standards. At the time, a culture of rule-bending at the agency prevailed—one division assigned itself the number 007 and joked it had a “license to kill” bureaucracy. In December 1994, the FDA approved OxyContin. This opened the door for Purdue to broadly market the drug at higher doses and for long-term use—well beyond the scope of the original trial data. And the agency’s OK for chronic pain, instead of just acute pain, was worth billions to the pharmaceutical industry. My Businessweek investigation also uncovered a pattern of the FDA bowing to political pressure and being reluctant to revisit past errors. And the FDA reviewer who cleared OxyContin’s approval later took a job at Purdue.  Photo illustration: Joan Wong; Photos: AP Photo, DEA, Getty Images (2) At 60 Minutes, I had reported on the tactics of opioid salespeople, pill mill doctors, the failures of federal regulators to rein in drug distributors—all factors in the US epidemic. I also dug into the FDA’s record. Regulatory filings, internal correspondence, litigation discovery and interviews pointed to a pattern: The agency repeatedly approved opioids and labeled them for non-cancer chronic pain without sufficient data. Where were FDA lawyers at that time? “Surprisingly, legal reviews are not routine,” Seth Ray, former counsel in the FDA’s Office of Chief Counsel, said this week. “At a high level, they don’t think they need to be bound by law or the office of chief counsel. Lawyers can be seen as an obstacle.” Ray, whose concerns were echoed by other former top attorneys in the office I spoke to, said he hopes Makary will now implement a system of legal review. But former FDA Chief Counsel Peter Barton Hutt suggests Makary’s use of the word “illegal” is a political move. In practice, he says, the agency can approve anything it wants without strictly following the statutes. If the FDA rigorously followed regulations such as the one requiring “adequate and well-controlled trials,” hundreds of approved oncology and rare disease drugs would have to come off the market. He worries that the FDA has squandered its credibility. Edwin Thompson, founder of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Research Services, says he’s at a loss as to what the agency does next on prescription opioids. “I don’t know how a commissioner can put that in writing and not take the drug off the market,” he says. “The commissioner says his agency illegally approved the drug. If I were selling that drug right now, I wouldn’t ship another tablet.” Sign up for the Prognosis newsletter to get the latest in health, medicine and science—and what it means for you. You can read today’s featured story online here. |