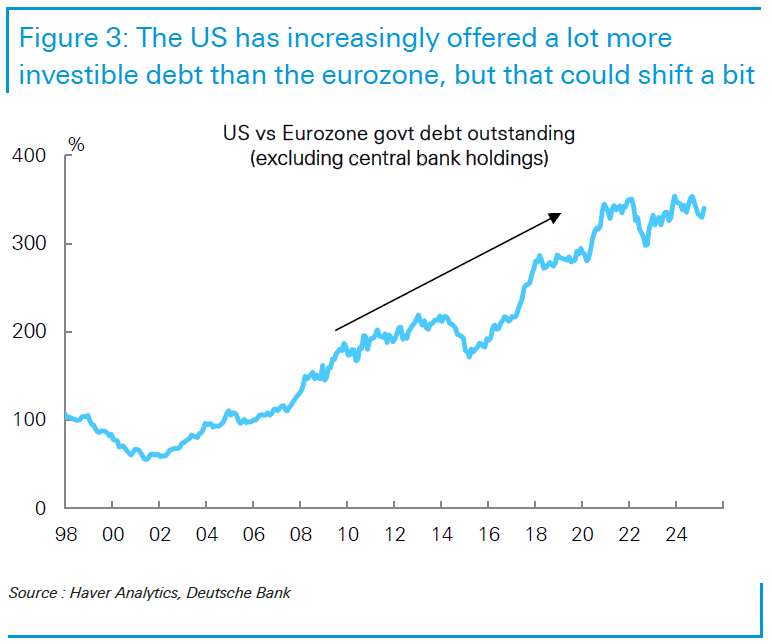

| Blink and you missed it. The historic downgrade of US sovereign debt announced Friday night only momentarily interrupted momentum. The S&P 500 rose 0.09% for its sixth consecutive daily gain, while bonds had a good day despite Moody’s negative judgment. After an initial selloff, the 10-year Treasury yield closed the day at 4.44%, 3.2 basis points lower for the day. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent’s dismissal of the agency as a “lagging indicator” of US fiscal policy looks to have been right. It had no significant short-term impact. That said, Moody’s nailed a broader truth — that US debt has surged. Germany’s post-Global Financial Crisis “debt brake” left it with space to borrow now. American debt kept rising and takes a bigger share of the economy than China’s. The chart is by Mansoor Mohi-Uddin of the Bank of Singapore: Even though Treasury debt is the linchpin of the world financial system, it is now lower-rated than 10 other countries: Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, and Switzerland. So there are alternatives, even if they’re nowhere near deep enough to soak up all the money in Treasuries. As Europe embarks on extra borrowing to bolster defense — at a stronger rating than Treasuries — there could be more triple-A bonds available to buy, as Deutsche Bank AG illustrates:  Source: Deutsche Bank The rally shows that the “End of the US” trade was overdone, but the fact remains that overvaluation got so extreme earlier this year that some adjustment was vital. US stocks have recouped only a little of the ground lost to the rest of the world: This is in part due to the dollar. The 2011 downgrade by Standard & Poor’s spurred what now looks like catharsis, which then started a decade-long rise. This time, particularly in real terms (accounting for differences in inflation), the dollar looks expensive. Investors didn’t feel over-exposed to US assets 14 years ago. That has changed, suggesting room for the dollar to fall further: As Deutsche shows, the consistency of the dollar’s overvaluation compared to purchasing power parity (the exchange rate at which goods cost the same in two currencies) is unprecedented. Moody’s judgment is symptomatic of the appetite to bring it down: A strong dollar is a problem for the US when policymakers are prioritizing exporters’ competitiveness. The administration is wont to complain that the rich dollar is a “non-tariff barrier.” That explains why sudden weakening against some of the Asian currencies that stand to be most affected by tariffs was greeted as evidence that these things are negotiable — and that the underlying direction of the dollar is downward: Slack foreign demand for Treasuries also weakens the dollar. Foreign bidders don’t participate directly in Treasury auctions, but have their bids placed by intermediaries — hence “indirect.” Apollo Group’s Torsten Slok points out that such participation in 30-year Treasury auctions has trended sharply down recently: All else equal (it never is, but economists assume as much), higher bond yields would raise the dollar compared to other currencies. But this time, expectations of higher fed funds rates have had no impact of any significance on it. (If you’re reading this on the terminal, try opening this chart in GP to see the two lines on the same chart): Similarly, the spread of Treasuries over German bunds hasn’t bolstered the dollar against the euro. Again, try opening this in GP: This relationship is even clearer when comparing real yields, as in this chart from Mizuho’s Jordan Rochester. The dollar is less attractive to foreign investors than a few months ago, for reasons beyond the standard macro drivers: That implies a further reason for weakness ahead. Manish Kabra of Societe Generale SA suggested that ongoing reduced foreign ownership of US Treasuries meant that the Fed would be be the lender of last resort — and would eventually be forced to ease. “This is why we say ‘Great Rotation for long-term,’ i.e. Fed moves will drive the US dollar weaker.” |