|

Is your team building or scaling AI agents?(Sponsored)

One of AI’s biggest challenges today is memory—how agents retain, recall, and remember over time. Without it, even the best models struggle with context loss, inconsistency, and limited scalability.

This new O’Reilly + Redis report breaks down why memory is the foundation of scalable AI systems and how real-time architectures make it possible.

Inside the report:

The role of short-term, long-term, and persistent memory in agent performance

Frameworks like LangGraph, Mem0, and Redis

Architectural patterns for faster, more reliable, context-aware systems

The first time most people interact with a modern AI assistant like ChatGPT or Claude, there’s often a moment of genuine surprise. The system doesn’t just spit out canned responses or perform simple keyword matching. It writes essays, debugs code, explains complex concepts, and engages in conversations that feel remarkably natural.

The immediate question becomes: how does this actually work? What’s happening under the hood that enables a computer program to understand and generate human-like text?

The answer lies in a training process that transforms vast quantities of internet text into something called a Large Language Model, or LLM. Despite the almost magical appearance of their capabilities, these models don’t think, reason, or understand like human beings. Instead, they’re extraordinarily sophisticated pattern recognition systems that have learned the statistical structure of human language by processing billions of examples.

In this article, we will walk through the complete journey of how LLMs are trained, from the initial collection of raw data to the final conversational assistant. We’ll explore how these models learn, what their architecture looks like, the mathematical processes that drive their training, and the challenges involved in ensuring they learn appropriately rather than simply memorizing their training data.

What Models Actually Learn?

LLMs don’t work like search engines or databases, looking up stored facts when asked questions.

Everything an LLM knows is encoded in its parameters, which are billions of numerical values that determine how the model processes and generates text. These parameters are essentially adjustable weights that get tuned during training. When someone asks an LLM about a historical event or a programming concept, the model isn’t retrieving a stored fact. Instead, it’s generating a response based on patterns it learned by processing enormous amounts of text during training.

Think about how humans learn a new language by reading extensively. After reading thousands of books and articles, we develop an intuitive sense of how the language works. We learn that certain words tend to appear together, that sentences follow particular structures, and that context helps determine meaning. We don’t memorize every sentence we’ve ever read, but we internalize the patterns.

LLMs do something conceptually similar, except they do it through mathematical processes rather than conscious learning, and at a scale that far exceeds human reading capacity. In other words, the core learning task for an LLM is simple: predict the next token.

A token is roughly equivalent to a word or a piece of a word. Common words like “the” or “computer” might be single tokens, while less common words might be split into multiple tokens. For instance, “unhappiness” might become “un” and “happiness” as separate tokens. During training, the model sees billions of text sequences and learns to predict what token comes next at each position. If it sees “The capital of France is”, it learns to predict “Paris” as a likely continuation.

What makes this remarkable is that by learning to predict the next token, the model inadvertently learns far more. It learns grammar because grammatically correct text is more common in training data. It learns facts because factual statements appear frequently. It even learns some reasoning patterns because logical sequences are prevalent in the text it processes.

However, this learning mechanism also explains why LLMs sometimes “hallucinate” or confidently state incorrect information. The model generates plausible-sounding text based on learned patterns that may not have been verified against a trusted database.

Gathering and Preparing the Knowledge

Training an LLM begins long before any actual learning takes place.

The first major undertaking is collecting training data, and the scale involved is staggering. Organizations building these models gather hundreds of terabytes of text from diverse sources across the internet: websites, digitized books, academic papers, code repositories, forums, social media, and more. Web crawlers systematically browse and download content, similar to how search engines index the web. Some organizations also license datasets from specific sources to ensure quality and legal rights. The goal is to assemble a dataset that represents the breadth of human knowledge and language use across different domains, styles, and perspectives.

However, the raw internet is messy. It contains duplicate content, broken HTML fragments, garbled encoding, spam, malicious content, and vast amounts of low-quality material. This is why extensive data cleaning and preprocessing become essential before training can begin.

The first major cleaning step is deduplication. When the same text appears repeatedly in the training data, the model is far more likely to memorize it verbatim rather than learn general patterns from it. If a particular news article was copied across a hundred different websites, the model doesn’t need to see it a hundred times.

Quality filtering comes next. Not all text on the internet is equally valuable for training. Automated systems evaluate each piece of text using various criteria: grammatical correctness, coherence, information density, and whether it matches patterns of high-quality content.

Content filtering for safety and legal compliance is another sensitive challenge. Automated systems scan for personally identifiable information like email addresses, phone numbers, and social security numbers, which are then removed or anonymized to protect privacy. Filters identify and try to reduce the prevalence of toxic content, hate speech, and explicit material, though perfect filtering proves impossible at this scale. There’s also filtering for copyrighted content or material from sources that have requested exclusion, though this remains both technically complex and legally evolving.

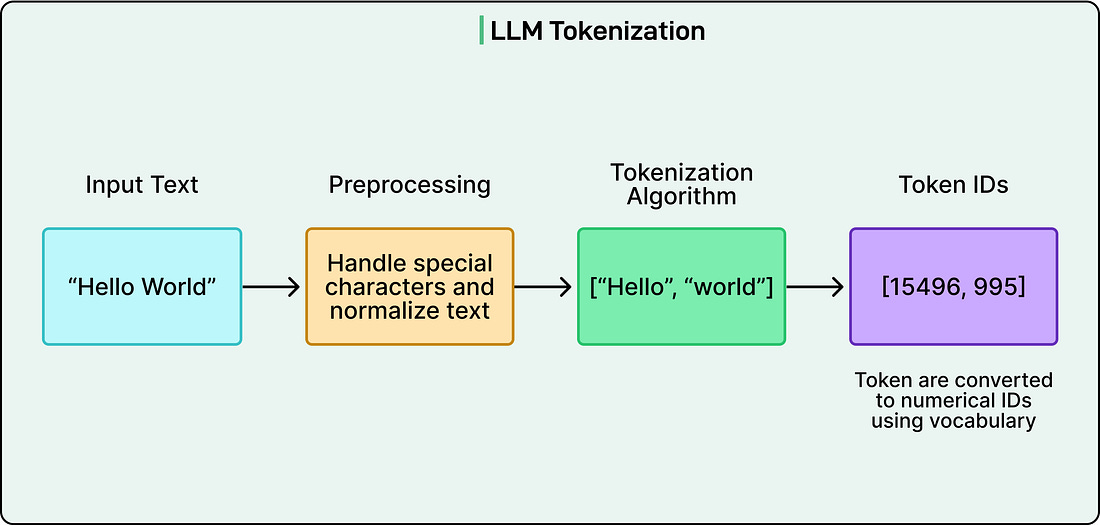

The final preprocessing step is tokenization, which transforms human-readable text into a format the model can process.

See the diagram below:

Rather than working with whole words, which would require handling hundreds of thousands of different vocabulary items, tokenization breaks text into smaller units called tokens based on common patterns. A frequent word like “cat” might be a single token, while a rarer word like “unhappiness&#