|

Japan’s political uncertainty is resolved for a while by the bold choice of Sanae Takaichi, a feisty veteran, as its first female prime minister. Her elevation seemed highly unlikely until she won the Liberal Democratic Party’s internal election three weeks ago, and since then she has endured a fracture in the governing coalition. She now has a new partner, and with it the premiership. It’s an exciting development, but what should markets expect?

The agenda of Takaichi and her allies in the Japan Innovation Party is plainly market-and-growth friendly, as far as it goes. Mansoor Mohi-Uddin, chief cross-asset strategist at the Bank of Singapore, summarizes as follows: - First, fiscal policy is likely to be eased further now. Takaichi has ordered a fresh supplementary budget to cushion the impact of inflation including subsidies for electricity and gas payments and regional grants.

- Second, both the LDP and JIP favour stronger defense spending given the geopolitical challenges Japan faces in Asia.

- Third, the LDP and JIP are also keen to improve energy security and lower costs by restarting Japan’s dormant nuclear power stations.

- Last, the Bank of Japan may keep its overnight call rate on hold at 0.50% for longer.

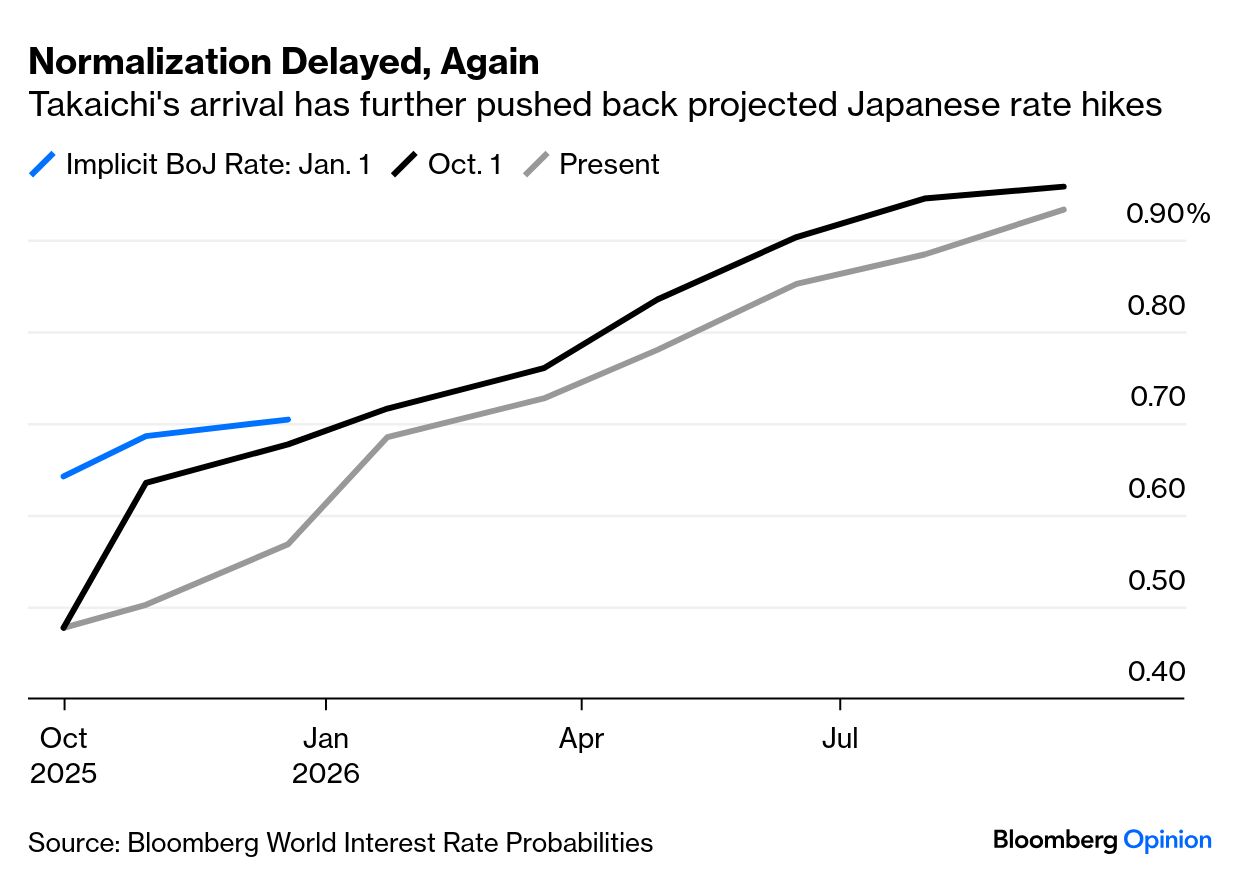

On top of a laundry list of pro-growth policies, the scope for major repatriation of Japanese assets is already obvious, irrespective of political direction. For the first time in two decades, you can actually get a better yield from 10-year Japanese Government Bonds than from dividends in the S&P 500. The extreme incentives to put money in the US are gone, even without making any recourse to arguments about declining American exceptionalism: But she faces issues persuading investors that Takaichi-nomics will be different from Abenomics, as practised by her political mentor, the late Shinzo Abe. When he came to power for the second time late in 2012, he launched a pro-growth campaign that involved rock-bottom interest rates and devaluing the yen. The yen took a huge step down after Abe’s arrival. But the point in assessing Takaichi’s options is that it took another one in 2022, as the Bank of Japan decided not to raise rates while all its counterparts did. The yen is now startlingly cheap, as Points of Return has emphasised. There is no scope for yet another leap lower on anything like the scale that Abe oversaw in 2012. And yet Takaichi has still had a significant impact on expectations of the BOJ. While a rate hike next week was at one point deemed likely by the markets, that has shifted with her ascendance. As she last year described plans for a rate hike as “stupid,” that might seem reasonable. But overnight index swaps view this as only a matter of timing. By early next year, the implicit course of interest rates is only slightly changed from what was predicted at the beginning of this month, before Takaichi won the LDP leadership:  The sharp weakening in the yen since Takaichi’s party victory hinges on the belief that she will mean a looser BOJ. This is questionable. The term of Governor Kazuo Ueda has several more years to run, and Takaichi has tamped down the dovish rhetoric of late. Udith Sikand of Gavekal Research points out that her coalition partners advocate respect for BOJ independence, while US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has blamed the yen’s undervaluation on the BOJ for not raising rates enough. Takaichi won’t want to annoy Washington more than necessary. Further, Sikand cautions: BOJ officials continue to hint that a rate increase next Thursday is possible. If the BOJ comes out with an uncharacteristically hawkish message — as it did in July 2024 — to assert its independence, the repricing of JGBs and the yen could be swift.

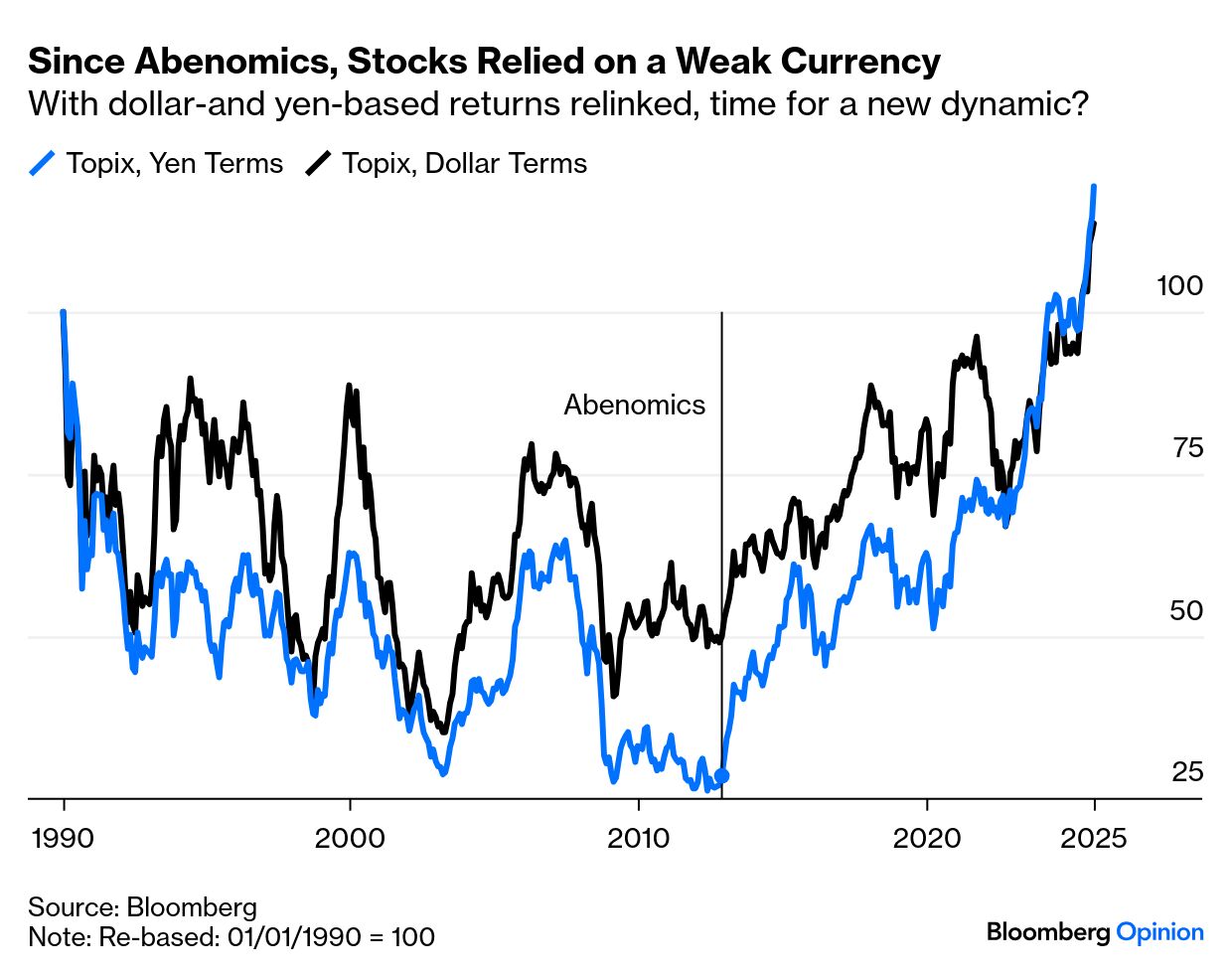

All of this implies bad things for the established bullish case to buy Japanese stocks, which is that anything bad for the yen is good for the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Over the last 20 years, their relationship has looked almost linear: There are problems with this approach. Japanese companies aren’t solely exporters, and its multinationals make many of their products outside Japan. A weakening yen doesn’t necessarily help them that much. But it’s understandable that the arrival of Abe’s mentee in the top job would revive interest in this trade — since the turnaround that he started over a decade ago, the Topix index in yen has made up all of the gap with the dollar-based version:  The Takaichi opportunity may be less in repeating the steps Abe took than in pressing through with corporate governance reforms that he never completed to his satisfaction. Japan has a lot of listed companies. They suffer from excessive capacity and competition, and Takaichi is on the record complaining about it. If regulators can finally persuade managements to sell and allow consolidation, or sell to private equity buyers, the results could be galvanic. Small companies’ performance in this decade has been terrible. The opportunity is obvious: Japan also has far more cheap companies than anyone else. There’s a reason for this, as its firms aren’t great at making profits. But comparing the earnings multiples on MSCI’s value indexes for the US and Japan suggests that there must be bargains to be found, if Takaichi can succeed in catalyzing profitability: If Takaichinomics is to work, as it well might, it will be by completing Abenomics and moving to the micro, and not by repeating the macro. Rather than betting against the yen, it’s time to start running the rule over Japanese companies. |