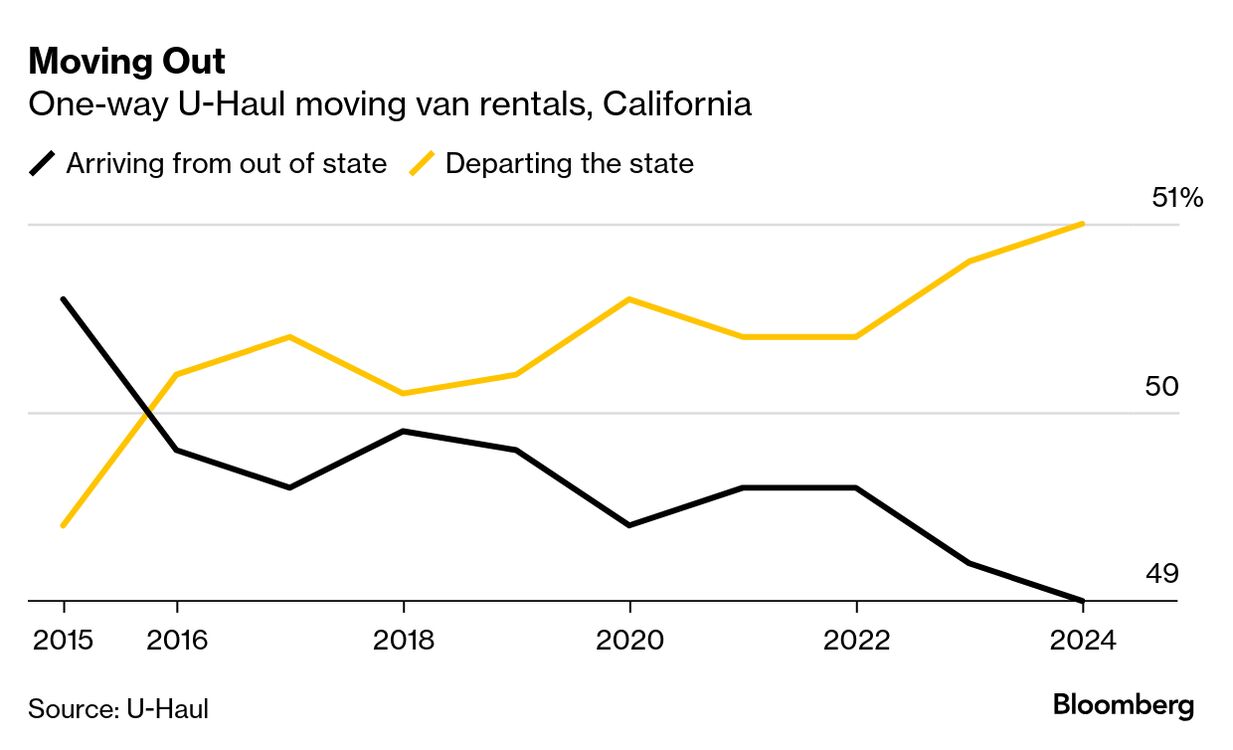

| Our new cover story is live now, an interview with California Governor Gavin Newsom, who’s spoiling for a fight with President Donald Trump. In today’s newsletter, Bloomberg Businessweek Editor Brad Stone writes about how Newsom’s record in the state might affect his future ambitions. Plus: China’s growing port portfolio, and nine founders making a difference in the world. If this email was forwarded to you, click here to sign up. There’s an old saying among politicos: “California is always on the ballot”—America’s most populous and productive state is in one way or another continually on the mind of the country’s voters. That’s palpably true this year, as the state considers a redistricting referendum meant to counter Republicans’ attempts to gerrymander the midterm elections in their favor, and as Governor Gavin Newsom, the subject of our November cover story, presents himself as a social media warrior ready to lead a listless Democratic Party. But if the nation’s voters are ever again asked directly whether America should look more like California—Newsom is near the top of every list of Democratic presidential hopefuls—they’ll have to consider an economic picture that is decidedly mixed. The state, as is often noted, is a powerhouse that generates 14% of the country’s gross domestic product and alone would have the world’s fourth-largest GDP, just ahead of Japan’s. It leads the country in confronting climate change by adopting renewable-energy and electric-vehicle standards. And as home to almost two-thirds of the leading global artificial intelligence companies, it has reestablished its primacy (if it was ever truly in doubt) as the world’s top incubator of the next new thing.  Photo illustration by Social Species; photos: Bloomberg (4); Getty Images (8) Along with these flexes, not to mention the glorious weather and stunning vistas, California also leads the country in less positive categories. It has the highest unemployment rate (5.5%), is tied with Louisiana for the highest poverty rate and regularly ranks at or near the bottom of most lists measuring high school graduation rates. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, sky-high prices for housing and other necessities, a visible homeless problem in major cities and perceptions of lawlessness have driven more people—and companies—out of the state than its enduring charms have lured them into it. “The mythology of California is that you could come here and remake yourself and build a middle-class living,” says Los Angeles-based political strategist Mike Madrid, who has advised both Democrats and Republicans. “That’s a quaint notion of the past. You can’t come here without a college degree and ever own a home, let alone support a family.”  The California dream arguably started to fade a few decades ago. After the Cold War, military bases closed, and aerospace giants like Northrop Grumman Corp. and McDonnell Douglas Corp., which helped fuel the state’s furious economic expansion, shrank or disappeared. The tech companies that replaced them employed far fewer people and concentrated wealth in the hands of relatively few shareholders and workers. There’s broad consensus that the state enacted bad policies, too, including labyrinthian regulations that made it hard to run a business and, crucially, to develop land and build more housing. According to the US Census Bureau, California’s population has slightly declined since 2020, while states like Texas and Florida have gotten larger. “It’s more than just housing. Development in all areas of California needs to be streamlined and more efficient. We’re making it costlier for individuals to live here,” says Jennifer Barrera, chief executive officer of the California Chamber of Commerce. One frequently identified villain is the 55-year-old California Environmental Quality Act, which makes it onerous for companies to get the necessary approvals to build things and too easy for everyone from environmentalists to disgruntled neighbors to stop them. This summer, Newsom signed two bills that overhauled the state’s permitting process, exempted high-density housing from CEQA and shielded qualifying projects from expensive and time-consuming litigation. Critics pointed out the reform came relatively late in the governor’s second and final term and was a response to President Donald Trump’s surprising success in the state in the 2024 election. But the move helped recast Newsom as an “abundance” Democrat—part of the fashionable movement of liberals who want to remove barriers to new construction and economic growth. In his interview with Bloomberg Businessweek, Newsom criticized Trump’s economic policies, took aim at what he calls the administration’s engagement in “crony capitalism,” and generally displayed his brand of direct and obscenity-laced political pugilism that’s helped him capture public attention lately. He also dodged any talk of running for president in 2028 and conceded that the perception of his state isn’t all that great right now. “I’m not naive about California’s status in the national electorate. I’m not a fool. Just the opposite—I’m consciously battling all this, including how vulnerable we are on the two key issues that are completely legit critiques: housing and homelessness,” he said. “I’m quite offended about the status quo myself.” Read the cover story: ‘I Want to Win’: Inside Gavin Newsom’s Plan for Taking On Trump |