|

A few years ago, it looked as if the U.S. and China might battle over global hegemony and preeminence. But this looks less likely now, thanks to America’s own behavior. Under Trump 2.0, the U.S. has alienated many of the key allies it would have needed in order to match China’s market size and manufacturing acumen, leaving America standing alone against a country four times its size. Tariffs have hobbled America’s already tottering manufacturing sector. Just a few months after Trump’s inauguration, the idea of a democratic world led by the United States standing up to challenge China’s rise now seems more than a little far-fetched. Meanwhile, China continues to bully and overpower Trump in trade negotiations.

This basically leaves China as the world’s preeminent power by default. The likeliest outcome is that this will be a “Chinese century” — though it won’t look quite like the “American century” did, because China will use its power and influence very differently than the U.S. did:

On the other hand, nothing is certain. Rising powers have squandered their moment in the sun and cut short their own rise in the past. In fact, this is not such an uncommon outcome. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were four rising powers — the U.S., Germany, Japan, and Russia. Of those four, only the U.S. arguably realized its full potential. Germany and Japan engaged in total wars against coalitions of opponents they couldn’t defeat, while Russia embraced one dysfunctional political-economic system after another until it slowly ground itself down.

So it’s possible that even without being overmatched by a U.S.-led coalition, China will stumble all on its own over the next three decades or so. That would certainly come as a relief to China’s increasingly alarmed neighbors, and it would provide critics of the CCP with the occasion for plenty of gloating. I don’t think it’s likely, but it’s worth thinking about the factors that could make China disappoint its most ardent fans.

Demographics

In general, China’s demographic situation seems to be the threat that its detractors have fixated on the most. I occasionally see headlines like “China Faces Economic Blow From Population Crisis”, or “Will China’s Demographics Constrain Its Foreign Policy?”. Some people even think that China’s rapid aging and shrinking population make it a paper tiger:

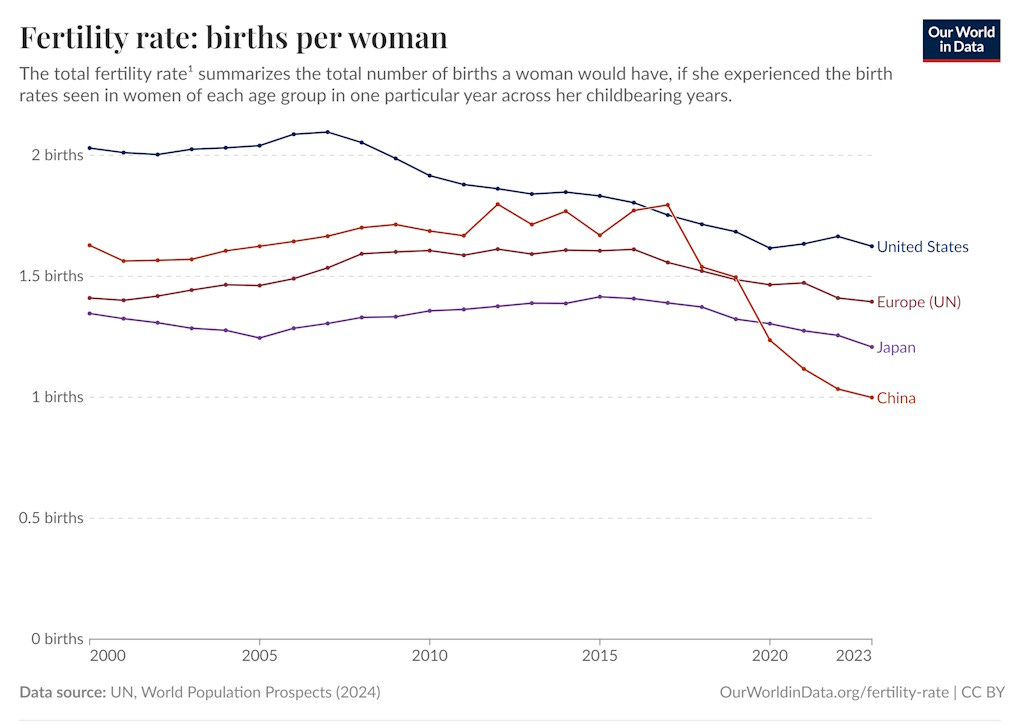

On one hand, there is something to this. Almost all nations are headed for major demographic problems, but China’s will be especially challenging. Its total fertility rate has fallen to 1.0 — one of the lowest in the world, and lower than Japan, Europe, or the U.S.

This means that China’s population will eventually halve every generation — or worse, if fertility continues to fall. A shrinking population is a big economic problem, since it A) forces young working people to support more and more retirees, B) probably reduces productivity growth, and C) discourages domestic investment.

Nor do I think robots will solve the problem, as China’s boosters often argue. If labor and capital retain significant complementarity, then China will need humans to work alongside the robots, just like everyone else. And if robots replace h