|

Stocks are up a lot over the past year. If you put $100,000 into an S&P 500 index fund a year ago, you would have about $119,000 now, counting dividends:

That’s not bad, eh? A free 19,000! Of course it’s not technically income — you still have to sell the stock in order to actually use that money to buy anything, at which point you’ll pay capital gains tax. But consider everything you had to do to earn that $19,000:

Press a button that says “buy S&P 500 index fund”

…That’s literally it! That’s all you have to do!

This strikes some people as unfair. After all, the median personal wealth in America is around $112,000, meaning that almost half of Americans don’t even have $100,000 to invest. If you don’t have much wealth at all, then the only way for you to get $20,000 — probably — is to work a bunch of hours. At 19 an hour, that’s 1000 hours — more than half of a typical working year!

That naturally strikes a lot of people as unfair. Why should poor people have to toil away for huge portions of their lifetime, while rich people can make money appear automatically in their accounts with the touch of a button? This is the question of desert (who deserves money), and it’s something a lot of people think about and care about with regards to the economy.

Even if you don’t think making capital income is inherently unfair, there’s a second question, which is: Why do we need that kind of thing for our economy? If people are getting compensated for pressing a button that says “Buy an S&P 500 index fund”, then presumably this button-press must be necessary for our economy somehow. But why?

It’s obvious why we need workers. It’s clear why we need real investment — building machines, structures, vehicles, and so on. It’s obvious why we need entrepreneurs. But why does production depend crucially on some guy pressing a button that says “Buy an S&P 500 index fund”? This is the question of utility, and it’s actually a question of whether there could be a more efficient way to design our economy. (In fact, as we’ll see, this ends up actually being connected to the question of “Who deserves money?” But it’s good to conceptually separate them in our minds.)

These are very basic questions that we don’t think about very often; capitalist economies are just all set up this way, and they all work pretty well in terms of making the average person rich, so we don’t question it at a deep level. But some people do! For example, Matt Bruenig, the socialist writer, recently wrote:

This touches both on the question of why investors deserve capital income, and on the question of what function investors perform in the economy. So let’s think a little bit about those questions.

What do investors give up in order to get financial income?

In fact, the question of “who deserves money?”, like all moral questions, is subjective. People disagree about this all the time. Some people think welfare is fine, other people think people should work for their money, and so on. There’s no one provable universal answer to the question of whether you deserve to get money by buying an S&P 500 index fund.

But we can simplify this question if we assume some kind of moral principle. And one pretty common principle is fairness. If you get something, it sort of seems fair that you should have to give up something in return.

For workers, it’s obvious what they’re giving up to earn a wage. Work is hard and annoying (otherwise they wouldn’t have to pay you to do it), and it takes up a lot of your time. So the sacrifice involved is clear. But what does an investor sacrifice just by pressing a button?

Well, the first thing they sacrifice is consumption. Investing money is a form of saving, and saving means you can’t consume. If I buy $100,000 of an S&P 500 index fund, it means I can’t spend $100,000 on…um…whatever people spend that much money on. A Lamborghini? Throwing lavish parties? A really really huge amount of Percy Pig candies? Whatever it is, I can’t buy it; in order to get that return on my stock investment, I’ve got to lock up my money for a while.

Locking up my money and forgoing consumption for a year might not be as painful as slaving away behind a cash register for 1000 hours, but it’s not nothing.

But that’s not actually the only thing that investors give up. They also take risk. Stocks usually make money (at least in the U.S.), but sometimes they crash. This isn’t just painful to watch when it happens; it’s also anxiety-inducing at the time you invest the money. When you buy an S&P 500 index fund, you have to wonder if you’re going to need to sell that stock to raise cash — for a medical emergency, or for your daughter’s wedding, or to spend in retirement — at the exact time when the market is way down.

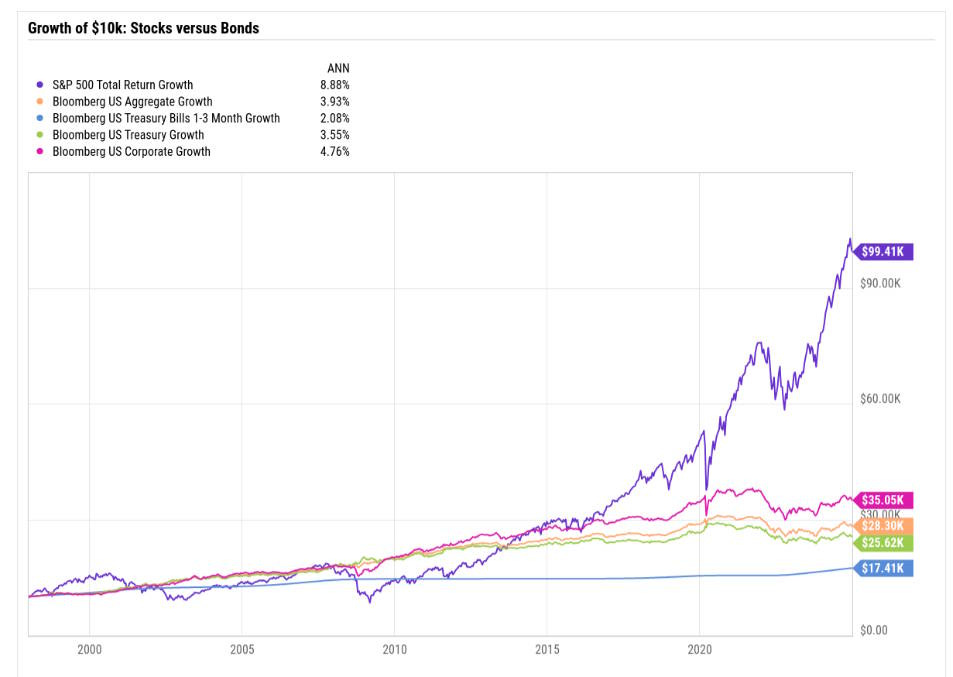

In general, riskier assets tend to give you higher returns. For example, stocks are riskier than bonds, since they tend to crash more often — and crash harder. But over a long time, investing in stocks tends to give you more money than investing in bonds. Here’s a comparison of U.S. stocks (dark blue) vs. U.S. treasury bonds since 1997:

|

As you can see, stocks actually did worse than bonds between 1997 and 2013 — sixteen years! If a stock investor needed to retire or pay a big medical bill during that 16 years, they were out of luck. But eventually stocks beat bonds. And you can see this same pattern throughout U.S. history (and in most other countries).¹

In finance, we call this the “risk-reward tradeoff”.²

The morality of the risk-reward tradeoff