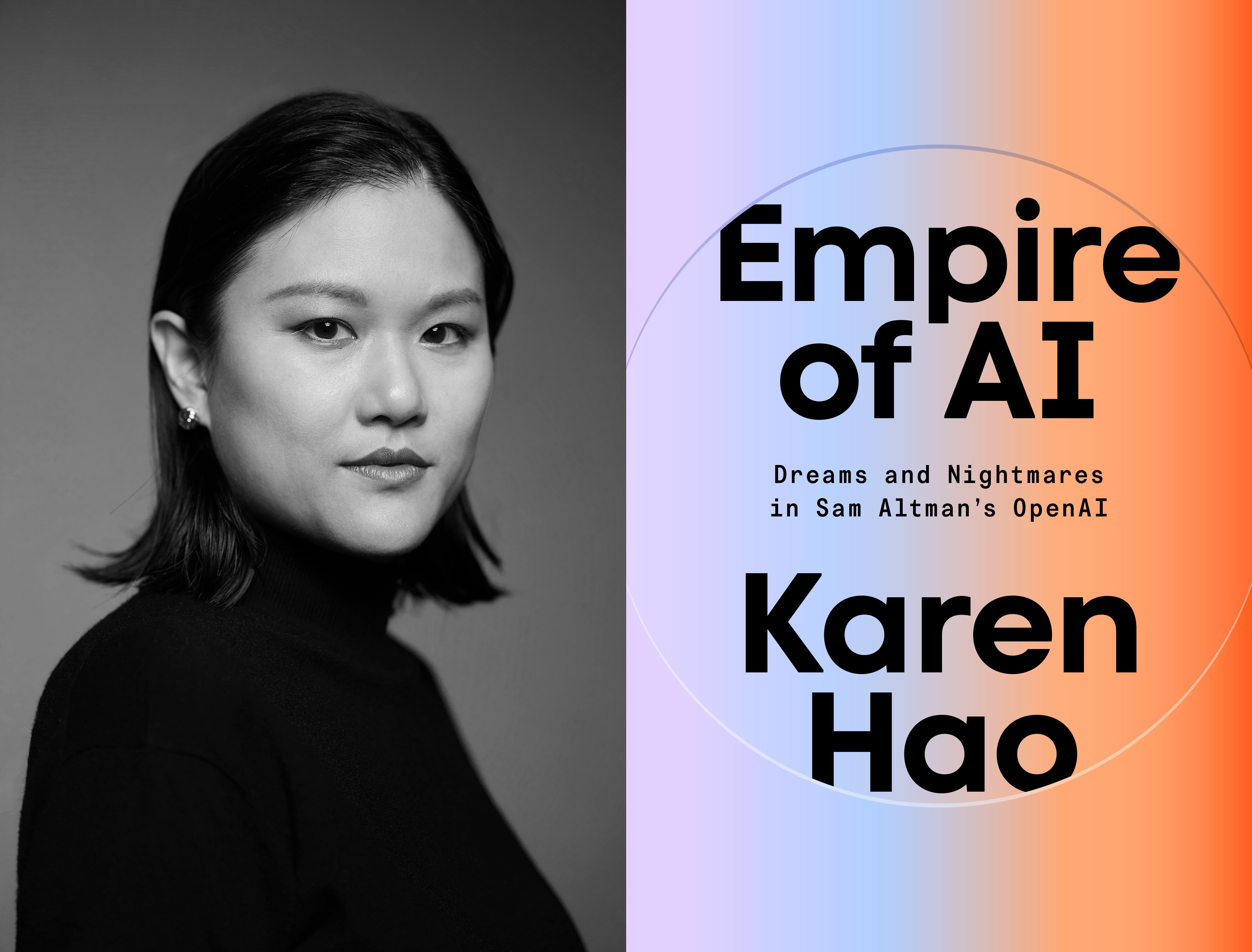

| Artificial intelligence is arguably the defining technology of our era, reshaping industries, geopolitics and the nature of human labor. At the center of this transformation is OpenAI, the San Francisco-based company behind ChatGPT, whose meteoric rise has sparked both awe and alarm. Once an idealist nonprofit lab, OpenAI has evolved into a multibillion-dollar juggernaut with deep ties to Microsoft and growing influence over global tech policy. As governments scramble to regulate and competitors race to catch up, questions around power, accountability and ethics loom large. Karen Hao has spent years investigating this revolution, having covered AI as a journalist at the MIT Technology Review and the Wall Street Journal. Through her reporting and interviews with insiders, the former MIT-trained engineer, who’s currently based in Hong Kong, has published her first book, Empire of AI. It examines OpenAI’s internal tensions, its charismatic CEO Sam Altman and the broader consequences of Silicon Valley’s ambition. We caught up with Hao to discuss the making of the book, fears over China’s rise in the field and what the future of AI may look like. —Yi Luo One of the unique concepts in your book is “AI colonialism.” What does that mean in practice? The parallels are stark: resource extraction of land, energy and data; labor exploitation, especially in the Global South, where workers do horrific tasks like content moderation and model cleaning; and monopolized knowledge, with most AI researchers now inside companies instead of academia. Imagine if all oil and gas companies employed most of the world’s climate scientists — you’d get a distorted picture of the science. That’s what’s happening in AI. And then there’s the grand narrative of good empire vs. evil empire to justify expansion. The US tech industry is playing on Congress’s fear of China’s AI rise to lobby against regulation. The narrative has been very effective for tech companies.  Karen Hao's Empire of AI. Photographer: Shoko Takayasu; Penguin Press Why are US firms spending so much on AI while Chinese firms do it for less. Is this a bubble? Technically speaking, yes, it’s a bubble. The scale-at-all-costs approach is harmful and intellectually lazy. AI doesn’t necessarily need this amount of spending. You don’t need Manhattan-sized supercomputers to build strong models. There are already techniques that reduce computational costs while maintaining performance. DeepSeek is proof. Americans started this scale-first model, and now other countries are following suit. But these tactics, focused on expansion and dominance, are shaped by industry ideology, not inevitability. What are the alternatives to scaling as the dominant AI strategy? This is the trillion-dollar question. GPT-5 was a letdown — it wasn’t much better than GPT-4. That’s a strong signal that we need to invest in other approaches. Before GPT dominated, the field was heading in a different direction, toward tiny AI models. Researchers were exploring how to train powerful models using minimal data and computational resources. Some were even training models on mobile phones. Another promising area is neuro-symbolic AI, which combines rule-based systems with data-driven learning. Rule-based systems are deterministic. You know exactly what they’ll output. Data based systems learn and adapt quickly. The challenge with probabilistic models is that they sometimes produce erroneous results. Neuro-symbolic approaches could be more accurate, efficient alternatives. How do chip restrictions shape the future of AI development? Constraints could breed better science. China has the talent and strong academia-industry links, but limited access to top chips is pushing researchers toward more data- and compute-efficient methods. DeepSeek is a good example. China’s chip limitations are forcing innovation beyond what the US is doing. That pressure could accelerate alternatives to the scale-at-all-costs paradigm, potentially healthier for both the field and the planet. Has Sam Altman or OpenAI responded to you since the book’s release? No formal response. Before publication, Altman subtweeted advice to read two other books about him — mine was the unmentioned third, which ironically drew more attention to it. |