|

|

Hi, y’all. Welcome back to The Opposition. I hope everyone had a lovely Fourth of July weekend, even if it was briefly interrupted by the passage of Trump’s “Big Beautiful Bill”—which happens to be the subject of today’s newsletter. As you might recall, last week I wrote about how Democrats were feeling a little optimistic about the political opportunities that the bill offered them. Now some Dems are insisting that the party needs a reality check.

Thanks for reading. If you’d like to support our work or participate in the comments—and we’d love to hear from you!—sign up for Bulwark+ today. You won’t regret it!

–Lauren

Why Trump’s Bill Might Not Be the Elixir Dems Imagined

Democrats’ initial optimism is fading as the bill’s political reality sets in.

THE DEMOCRATIC PARTY has serious problems on its hands. This newsletter has covered them.

The party’s approval rating is at record lows; its own voters have little faith in leadership; and a challenging Senate map along with looming census changes will only make winning elections harder. The list goes on—but we won’t.

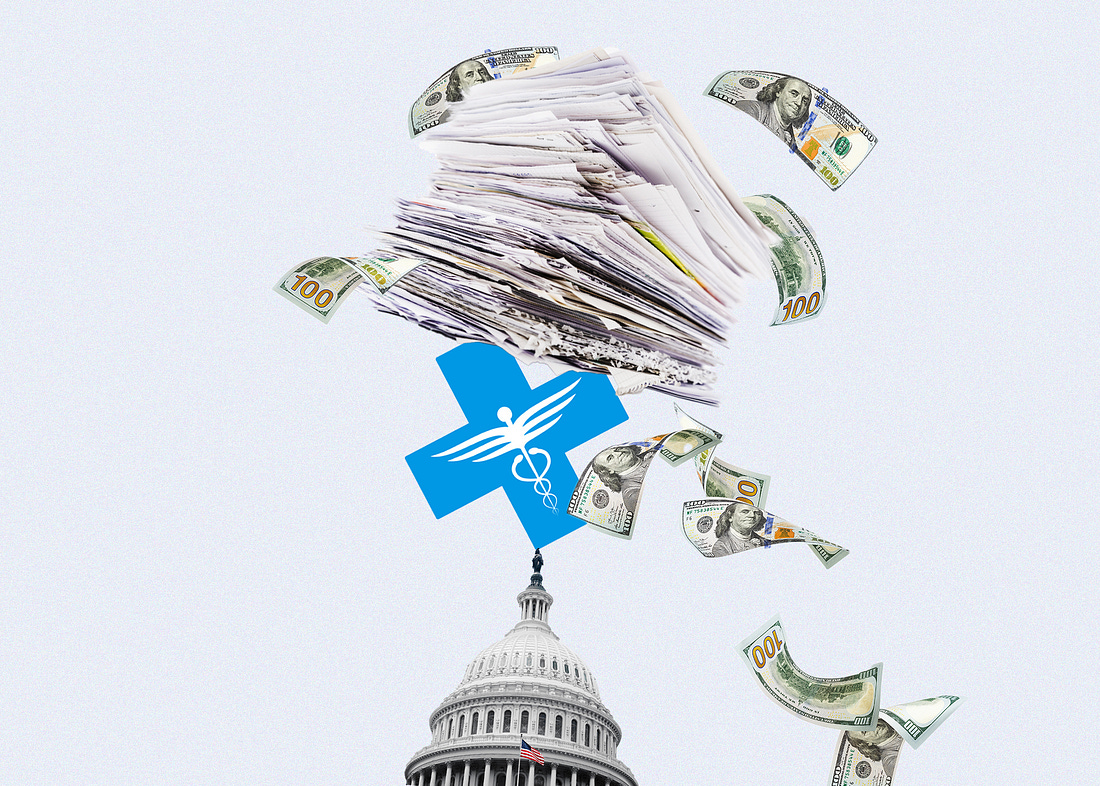

Against that morose backdrop, last week felt fundamentally different. Yes, the passage of President Donald Trump’s massive budget law was a setback for Democratic priorities—from the cause of public health to the fights for tax fairness and against malnutrition. But as a narrow electoral matter, the “Big Beautiful Bill” was a big political gift.

The bill’s polling is toxic. And the prospect of spending the next sixteen months attacking Republicans for voting to cut Medicaid and food-assistance programs, all to give tax breaks to the ultra-rich, is deeply enticing. Democratic operatives, for the first time since the election, were discussing whether they could flip the Senate by winning seats in red states like Nebraska and Alaska. And, frankly, it didn’t feel like total delusion.

That sense of opportunity, while not entirely gone, has clearly begun to fade. The euphoria Democratic leaders felt is now colored by fear that Republicans may not pay that steep a political price for the bill—or, rather, that focusing campaigns on the law may not be as surefire a strategy as they hoped.

Driving the change in mood are two factors. The first is how the bill itself is structured. The most politically toxic policy changes, like the cuts to Medicaid, won’t be fully implemented until after the midterm elections, while the more popular elements—such as $1,000 investment accounts for newborn children—will go into effect immediately. Some Democrats are concerned that their posture could alienate those parents aided by the new accounts.

“It’s a very clever bill. And I really worry about voters ultimately concluding, ‘Well, Democrats cry wolf again,’” said Celinda Lake, a top Democratic pollster.

Democratic officials are also concerned that the party has failed to present its own policy alternative. They worry that it’s not enough for Democrats to say, ‘We’re not Trump’—or, in this case, ‘We will undo the damage Trump did’—and expect that voters will instinctively reward them for that. In their greatest moments of despair, they wonder if the party may fumble the midterms because of a misreading of this moment.

“You can’t beat something with nothing,” warned Lake. “It’s not a foregone conclusion at all that we will win back the House. These seats are very difficult.”

Some of this looks to me like political scar tissue. One of the key lessons party leaders took from the 2024 election was that Democrats did a poor job explaining to voters what they believed in—let alone outlining a compelling economic agenda that would attract their support. For that reason, some strategists view Trump’s tax bill not as a target to attack but as an opportunity to offer an alternative vision.

“We have to figure out how to expand our brand in places that we’re losing, and that is a process that’s not going to happen overnight. So for me, the conversation around the ‘big beautiful bill’ and offering an alternative is as much about us restating our place as a party that fights for working families and the middle class,” said Steve Schale, a Florida-based Democratic operative, who added that it was a “missed opportunity” for Democrats to not put forward their own plan for cutting costs.

“I’m not that convinced that a lot of pieces of this bill are actually going to be that unpopular,” Schale lamented. “It’s not as black-and-white as I think some in D.C. feel like it’s going to be.”

WE’RE STILL A YEAR AND A HALF OUT from the midterms, so it’s worth acknowledging a few variables at this point. The first is, we don’t know what we don’t know. When Joe Biden passed his big COVID relief bill early in his presidency, the conventional wisdom held that the stimulus money would endear him to voters, and that Republicans would pay a price for not supporting it.

“They’ll get no credit” for those $1,400 checks, one senior administration official predicted at the time. “They’ll get no credit.”

Not only did the Republicans not need credit—Biden didn’t really get any.

The other variable to consider is that Democrats often tend to overthink things. An opposition party can (and probably should) present a galvanizing agenda. Certainly that was the lesson from 1994 and even 2010. But is it entirely necessary? Can you name the planks that Democrats ran on in 2018 other than having protected Obamacare from Trump’s efforts to repeal it?

For now, Democrats are focusing their ad campaigns and public comments on slamming Trump’s bill for its cuts to Medicaid, the impact it will have on rural hospitals, and other health care-related costs.

But in some corners, efforts have begun to help the party fill out the ‘What we will do’ part of the pitch to voters. Stef Feldman, a senior adviser in the Biden White House,