| This is Bloomberg Opinion Today, the commodification of elitism of Bloomberg Opinion’s opinions. On Sundays, we look at the major themes of the week past and how they will define the week ahead. Sign up for the daily newsletter here. Although it’s an integral part of my job to eliminate clichés, platitudes, prosaisms [1] and other banalities, I have a fondness for vast overgeneralizing about generations. I suppose the Lost Generation, the Greatest Generation and the Silent Generation were lost, great and silent, respectively. Baby boomers think they invented the world. Gen X can’t be bothered. Millennials think boomers ruined the world. Gen Z would like Gen X to shut the hell up. All are unfair. All are more than partly true. Where do you draw the lines? The rough rule of thumb for recent generations is 15-year increments, although boomers get 20 years because, well, they always get the most of everything. But I was born in 1966, my wife less than a year earlier: Are we different generations, me Gen X and her a boomer? My son was born in 1996: Is he millennial or Gen Z? In the early 1990s, I had lunch with Douglas Coupland, whose novel Generation X more or less popularized the term and set off a frenzy of generational stereotyping. [2] When I asked the obvious question, he told me he was born in 1961 and grew up in Vancouver. So America’s first Gen Xer was a Canadian baby boomer! Still makes me laugh. [3] You know who’s not laughing these days? Middle-aged millennials. Stephen Mihm has sympathy and a suggestion. “Often referred to as the ‘unluckiest generation,” millennials have had to adapt to rising costs of living and an unpredictable job market during their most formative career years. They are also hitting traditional life events — such as homeownership, marriage and parenthood — later than earlier generations, if at all,” he writes. For those put-upon snowflakes, he has a reading suggestion from 1976: Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life by the feminist writer Gail Sheehy. She was sort of the boomers’ Coupland: popularizing the idea of a “midlife crisis” long before the first millennial was born. “Millennials may find the book a useful guide to what they’ve experienced so far in life — and what to expect next — all without the kind of sermonizing or moralizing that their generation seems doomed to elicit,” adds Stephen. “That’s because Sheehy’s book advanced the then-heretical idea that crises that people endure as they grow older don’t reflect individual or generational shortcomings; they’re entirely normal.” Gen Z, meanwhile, has a serious generational shortcoming: savings. “Almost half of Gen Z – 49% – has decided saving for the future is pointless, according to a late May Credit Karma survey. These choices exemplify poor money management skills, a reality that has led Gen Z to blame schools for not teaching them more about how to manage their finances effectively,” writes Erin Lowry. “But of all the generations, Gen Z is the one with no right to complain about the lack of access to personal finance education in school. If any generation had a chance to teach themselves, it is them. Young adults today have grown up in a world full of easily accessible financial information and services, such as digital solutions for seemingly every method of budgeting.” They also grew up in a world full of easily accessible awfulness about their self-image. “#SkinnyTok is dead. Or at least that’s what TikTok wants you to believe after its recent ban of the hashtag promoting an extreme thin ideal. That might have appeased regulators, but it shouldn’t satisfy parents of teens on the app. An army of influencers is keeping the trend alive, putting vulnerable young people in harm’s way,” write Lisa Jarvis and my wonderful editor, Jessica Karl. “The rise of #SkinnyTok is in many ways a rehashing of the pro-eating disorder content of the past. In the mid-1990s it was Kate Moss and ‘heroin chic.’ Then came the Tumblr posts in the early aughts praising ‘Ana’ and ‘Mia,’ fictional characters that stood for anorexia and bulimia. Now, it’s 23-year-old influencer Liv Schmidt telling her followers to ‘eat wise, drop a size.’”  And, sadly, someone who might have helped counter-influence such trends — the 1990s MTV veejay Ananda Lewis — died on June 11. “She stirred a passion for journalism and current events among her young audiences — and that’s sorely lacking today,” writes guest columnist Candice Frederick. “That’s an especially sobering realization when you put it into context with the many challenges facing young Americans today: a president who’s threatening their democracy, attacks on transgender teens and the reinstated ‘involuntary collections’ on student loans, to name a few. While there’s no shortage of important issues for young people to talk about that get them engaged in the news, there are too few spaces that actually do so successfully.” While millennials are losing their hair and Gen Z their life savings, my slacker generation is getting … elitist? “Members-only clubs have always been part of the American economic and social fabric, from the Gilded Age clubs where Manhattan elites socialized to the country clubs in the suburbs,” writes Allison Schrager. “Membership was exclusive based on who you knew or what you achieved, and once you were tapped, social connections were made and business was taken care of. Clubs acted as a kind of screening mechanism.” And they are back — epitomized by Soho House, the London-based club that that spread like a chic social disease to Manhattan’s meat-packing district in 2003. “As private clubs have become more ubiquitous, their role in society has shifted: They tend to commodify elitism rather than enforce it. Getting in doesn’t depend on your wealth or cultural cache; all that matters is getting your name on the list and paying the initiation fee,” adds Allison. “Since there now seems to be a club for everyone, in every city, at every price, there is nothing especially elite or cosmopolitan about being in a club.” So Soho House is losing its cool just as millennials have the cash to join? Yet another devastating blow to the unluckiest generation. More Generation X Reading: What’s the World Got in Store ? - NATO summit, June 24: The US Is Making the World a More Dangerous Place — James Stavridis

- Jay Powell congressional testimony, June 24: The Fed Is Just as Confused as the Rest of Us — Jonathan Levin

- NYC mayoral primary, June 24: Why Has New York City Defied the Great American Crime Decline? — Justin Fox

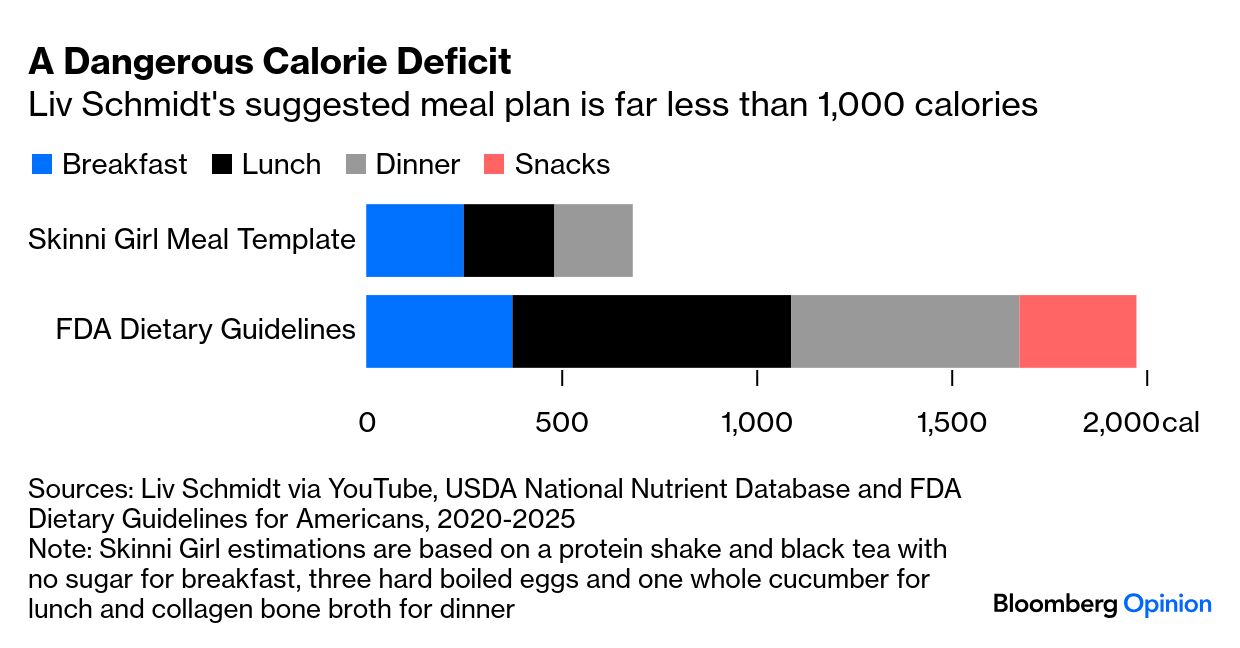

- Bank stress test results, June 27: Bessent’s Top Bank Reform Is Good for Markets — Paul J. Davies

Every generation has its defining cultural moments, and all the hoopla around the 50th anniversary of Jaws has me wondering: Was it Gen X’s first cinematic touchstone, or the boomers’ last? The movie is a sore spot for me: Being forbidden to go to R-rated movies at age 9, I was the only kid I knew who never saw it in the theater. So I’ll give Jaws to the boomers, and go with Star Wars for my tribe. Jaws a fantastic movie — the scene where the Hooper and Quint compare scars is incomparable — but there is one group that really, really wishes it had never been made: sharks. “The tale helped galvanize a fear of the ocean predators, and potentially contributed to a huge backlash,” Lara Williams writes. “While some were terrified of swimming after watching the movie, there were plenty of fishermen keen to prove their bravery by catching a shark. In 2014, Christopher Pepin-Neff, an associate professor in public policy at the University of Sydney, coined the term ‘the Jaws Effect,’ arguing that because the public believed the fictional story of a vengeful shark so completely, it justified anti-shark policies while taking conservation off the table.” But the problem isn’t really fishing tournaments or China’s affinity for shark fin soup: It’s large-scale commercial operations. “Sharks are in hot water, literally. A 2024 status report from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) found that a third of sharks, rays and chimaeras are at risk of extinction,” add Lara. “Predatory fish, such as hammerheads and silky sharks, often end up as bycatch – tangled in nets or ensnared on long lines intended to catch other species. Couple that with humanity’s growing taste for shark meat – now a multi-billion dollar industry – and you’ve got a group of species that barely stands a chance.” In retrospect, given that I’m now a scuba diver active in shark-preservation efforts, maybe my parents were right to shield my eyes from Spielberg’s epic at such an impressionable age.  Source: X Notes: Please do not send shark fin soup and feedback to Tobin Harshaw at tharshaw@bloomberg.net. |