|

It's OK not to be fat

Instead of moral problems, let's think of things like obesity as technological problems.

“O God, give us the serenity to accept what cannot be changed, the courage to change what can be changed, and the wisdom to know the one from the other.” — Winnifred Wygal

“Put the fork down!” — Denis Leary

I was going to write about the Elon-Trump blowup, but some things are just too ridiculous and extremely-online even for me, so I’ll skip it for now — at least until it starts seeming like it might have some economic ramifications. Instead I think I’ll write about something more optimistic, because my blog has admittedly been a little bit of a downer of late.

Over the past year, I lost about 45 pounds — about 20% of my maximum body weight. This didn’t seem like a particularly epic weight loss journey — certainly a lot less than the 70 pounds that Matt Yglesias lost a few years back. And unlike Matt, I didn’t have bariatric surgery to shrink my stomach. In fact, I didn’t even use Ozempic, Mounjaro, or any other weight-loss drug at all. All I did was eat less and exercise a little bit more. This seems like the kind of boring, everyday story that doesn’t really merit a blog post. But I think the way that I lost weight actually does have some interesting implications for how, as a society, we should think about weight loss — and about other personal struggles like addiction.

My not-so-epic weight loss journey

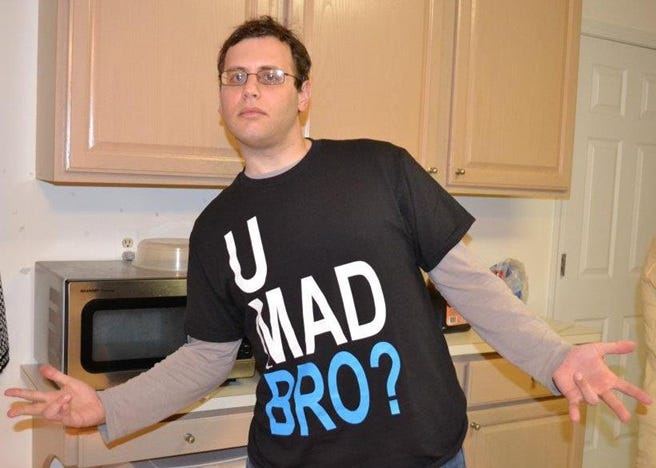

First, here’s the story. For most of my life, I haven’t been a fat guy — sometimes I would get a bit overweight, but I’d lose the weight after a year or so. This is what I looked like in grad school, at age 30:

But in 2020-22, I got much fatter than I had ever been in my life. My weight peaked at around 235 or 240 pounds. Part of this was from inactivity and overeating during the pandemic, but most of it was from migraines.

In mid-2021, for unknown reasons (maybe Covid?), I got chronic vestibular migraine. This wasn’t the painful kind of migraine, thankfully. But it meant that I was pretty much constantly dizzy, and felt like my head was stuffed full of rags. This was one reason I left Bloomberg and became a full-time blogger in late 2021; I couldn’t handle more than 4 hours of screen time per day, so I had to give up either my hobby or my job, and I chose to give up my job.

Anyway, one thing that triggered my near-constant migraines to get even worse was any drop in blood sugar. So I minimized the dizziness by constantly eating. As you might expect, this caused me to gain quite a lot of weight over two years’ time. For the first time in my life, I became obese.

Eventually the migraines got a lot less bad, and I decided it was time to lose the weight I had put on. I considered taking Ozempic or another weight-loss drug, but I decided to see how easy it would be to just lose the weight by eating less. Over the next year, I started paying attention to how much I ate. If it was “time to eat”, but I wasn’t hungry, I wouldn’t eat anything. And when I did eat, as soon as I felt like I wasn’t hungry anymore, I would stop eating. Basically, this is what a lot of Japanese people do in order to avoid becoming overweight.

That was the main thing I did. There were also a few other smaller things. I generally ate less dessert and sugary stuff, though I still ate some. I exercised more — mostly aerobic exercise. And I also ate less salt. This last one wasn’t actually for weight loss — I also had high diastolic blood pressure, so my doctor told me to cut down on salt. But I found that when I ate less salt, I got less hungry — possibly because I’d retain less water, which meant my stomach would shrink. (I drink a LOT of water, so I never got dehydrated.) Finally, I invented some dishes that tasted great without having much salt or sugar in them.

But the main thing was just only eating enough to stop feeling hungry. At first, this meant that I ate only a little bit less than usual. But as time went on, I noticed myself eating less and less each day, until eventually my food intake leveled out at maybe half of what it used to be. My assumption is that this was because my stomach was shrinking.

I am not an expert in weight loss. I have only a fairly shallow understanding of metabolism, the actions of macronutrients, and why certain diets lead to weight loss. But one thing I’m pretty sure of is that having a smaller stomach makes you want to eat less. The reason is because bariatric surgery, which makes people’s stomach smaller, is an incredibly effective technique for long-term weight loss. This is what Matt Yglesias used, and it’s what my friend (and occasional guest blogger) Armand Domalewski used. When I hang out with Armand, I always marvel at how quickly he gets full. He has a small stomach because of the surgery. There must be some kind of sensory feedback from your stomach to your brain, so that when your stomach gets full you stop feeling like you want to eat.

That was my guess, anyway. I figured that as long as it was working, I didn’t need to look too deeply into the mechanism — that would just “nerd-snipe” me and tempt me to overly complicate things.¹

And it did work, so I kept doing it. I’ve never really eaten breakfast; now I found myself eating only a very small lunch, or occasionally no lunch at all. Strangely, I had plenty of energy throughout the day — in fact, more energy than before I started dieting. If I exercised I’d start to feel hungry, and then I’d eat something until the hunger stopped, just like always.

This strategy didn’t lead to me losing weight at a spectacular pace — it was just about 5 lbs per month. Weight loss drugs or more severe diets can let you lose weight much faster than that. But I didn’t want to stress out my liver, or develop loose hanging skin, etc. 5 lbs a month was plenty for me, and over 9 months or so, I had lost pretty much all of the weight I put on from both the migraines and the pandemic combined. I should still lose about 15 pounds, which I think I’ll do now that I’m pretty sure I don’t have loose skin from the earlier weight loss.² I don’t expect it to be very difficult.

Self-control is about attention, not “willpower”

So what’s interesting about this story? It seems pretty boring; I ate less, I lost weight. Wow, who knew? But I realized, as I was doing it, that the difference between losing weight and not losing weight was just attention.

When I didn’t pay attention, I didn’t lose weight, because I kept eating after the point where I was no longer hungry. When I paid attention, I was able to control when I stopped eating.

Most people think that if you lose weight without the aid of drugs or surgery, it takes “willpower”. But what is willpower? I know there’s a whole huge psychology literature on the concept, and within that literature is some evidence that people have some sort of “reserve”, at least in the short term, that gets depleted when they try to endure pain or stay focused on a task. But when it comes to eating less, I find it more useful to think in terms of two distinct willpower-related concepts: pain tolerance, and attention.

Pain tolerance is being able to endure distress and discomfort. A lot of people think that this is what weight loss requires. After all, eating less makes you hungry, and hunger is painful and unpleasant. So a lot of people think that losing weight requires you to be hungry a lot, and to endure that pain.

For a lot of people, I think this introduces a moral dimension, or at least a self-worth dimension, into how they think about weight loss. They think that to succeed in losing weight requires toughness and strong motivation — you have to be tough enough to fight through constant hunger, and motivated enough to want weight loss even more than food.

This idea of weight loss as a personal test raises the stakes, because it’s not just your waistline that’s on the line, but your whole sense of self-worth. If you fail to lose weight at first, or if you hit a plateau and gain a few pounds back, the “willpower” model says that this means you’re a wimp, or that you just didn’t want it enough. This makes weight loss a terrifying prospect for people are scared of discovering that they just don’t have what it takes, and a source of anguish and despair for people who suffer even temporary setbacks.³

Except that’s just not how it went for me. I didn’t endure much pain at all. While losing weight, I was rarely hungry — maybe a little bit, for a short amount of time, but when I felt hungry I’d always go eat something. And because my strategy was to eat until I no longer felt hungry, whatever small hunger pangs had driven me to eat would be quelled.

Instead, attention was the key to my strategy. I realized that in the past, the times when I had gained weight — for example, when I was writing my dissertation — are when my attention was wholly occupied by something other than personal health. Whereas all I had to do in order to lose weight was focus on it.

I think this is a much emotionally healthier way to think about weight loss. A lot of people who can’t lose weight simply don’t have the time and energy to devote to it. I was lucky, because being a self-employed blogger gave me the flexible schedule I needed to give weight loss my full attention. But you can’t be expected to make weight-loss another part-time job, on top of the job you already have!

So instead, you should consider doing what humanity always does when we’re faced with constraints on our time and our labor: automate the task.

Technology solves this

In general, I think technological solutions to human problems are severely underrated. Progressive writers love to declare that “tech won’t save us”, and decry the vile techbros who think a magic venture-f